GSD with F#, or how I ported my blog to Jekyll

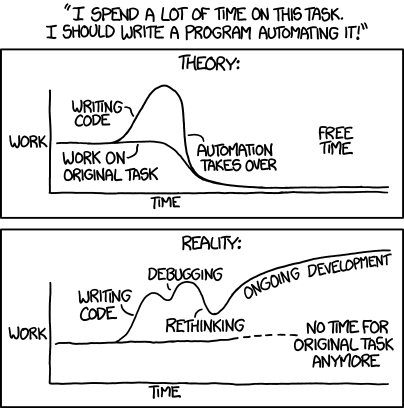

28 Aug 2016One of the reasons I use F# so much is that it’s an awesome scripting language to Get Stuff Done. Case in point: this blog. I recently decided to switch from BlogEngine.NET to Jekyll, which meant porting over nearly 9 years of blog posts (about 300), extracting html-formatted content from SQL and converting it to markdown. After a couple of weeks of manual process, I realized that at the current cadence, it would take me about a year to complete, and that by then I would probably have lost my mind out of boredom. Time for some automation with F# scripts!

My goal here was not to do anything fancy or elegant. I just wanted to get a dumb task over with, with minimum effort. Any code I would have to write would need to pass the following basic test: “will I be done faster with code, including the time it takes me to write it?”. In other words, quick-and-dirty hackery is perfectly OK; or, stated differently, don’t look for best practices in this post.

Extracting posts with the SQL Type Provider

First step: I need access to the data. All contents are stored in an antediluvian SQL Server instance somewhere on GoDaddy (don’t judge, we all have made some mistakes in our youth), so no luck using the shiny F# SQL Client - we’ll go for the F# SQL Provider instead.

All we need is a connection string:

#r "packages/sqlprovider/lib/fsharp.data.sqlprovider.dll"

open FSharp.Data.Sql

[<Literal>]

let connectionString = """Data Source=TOP-SECRET-CONNECTION-STRING"""

type sql = SqlDataProvider<Common.DatabaseProviderTypes.MSSQLSERVER,connectionString>

let context = sql.GetDataContext()

let posts =

context.Dbo.BePosts

|> Seq.take 10

|> Seq.toArray

We are now in good shape: we can start querying posts, and accessing all the relevant data:

Creating a post

Next, we need to take a blog post, and create a markdown document that complies with Jekyll expectations. Posts go into the _posts folder, the file name follows the pattern 2016-08-28-gsd-with-fsharp.md, and the content is organized along these lines:

---

layout: post

title: GSD with F#, or how I ported my blog to Jekyll

tags:

- F#

- Type-Provider

- Blog

---

Above the fold content goes here...

<!--more-->

... and the rest goes there.

Let’s leave the content part aside for a moment. All we need is to

- create a file name from the original publish date and slug,

- fill in the template with the original title and the formatted tags,

- save that text file in the correct folder.

Let’s start with a couple of utility functions:

open System

open System.IO

open System.Globalization

let textInfo = CultureInfo("en-US",false).TextInfo

let formatTag (tag:string) =

tag.Trim()

|> textInfo.ToTitleCase

|> fun text -> text.Replace(" ","-")

let extractTags (post:sql.dataContext.``dbo.be_PostsEntity``) =

post.``dbo.be_PostTag by PostID``

|> Seq.toList

|> List.map (fun tag -> tag.Tag)

|> List.map formatTag

let formatDate (date:DateTime) = date.ToString("yyyy-MM-dd")

let postsPath = @"C:\Users\Mathias Brandewinder\Documents\GitHub\mathias-brandewinder.github.io\_posts"

We use System.Globalization.CultureInfo to capitalize the tags consistently, so that extractTags can now take a Post from the SQL Provider, and convert all the attached tags to a list of capitalized strings. At that point, we are ready to go:

let processPost (post:sql.dataContext.``dbo.be_PostsEntity``) =

let postDate = post.DateCreated

let postTitle = post.Title

let postTags = extractTags post

let postSlug = post.Slug

let formattedTags =

postTags

|> List.map (fun tag -> sprintf "- %s" tag)

|> String.concat "\n"

let header = sprintf "---\nlayout: post\ntitle: %s\ntags:\n%s\n---" postTitle formattedTags

let content = "TODO"

let newPost = header + "\n" + content

let newPostName = (formatDate postDate) + "-" + postSlug + ".md"

let newPostFile = Path.Combine(postsPath, newPostName)

File.WriteAllText(newPostFile,newPost)

We take in a post, extract all the information we need, basically fill in the blanks in the template, and save it.

Is it pretty? Nope. Does it get the job done? Yes.

There are minor flaws (I’d prefer the tag Fsharp to be formatted as FSharp for instance), but this is good enough, I am fine with fixing this by hand. Moving on.

Converting html to markdown

The last missing piece here is the post content itself. post.PostContent gives us back a string, the html formatted contents. We could probably leave most of it as-is, but this would be a bit sad. The beauty of markdown is that it is fairly human-readable even in raw form, so I’d much prefer to convert from html to plain markdown.

This is not too complicated. Posts mostly follow the same structure, and, at the top level, are a sequence of either:

- “Chapter” header

<h2>/</h2>, - Paragraph

<p>/</p>, - Code block, delimited by

<pre class="brush: fsharp; ...">/</pre>.

Within paragraphs, besides plain text, we can also find:

- Images, with the image location and some extra information

<img src="http://url/pic.jpg" ..., - Links, with the text and url

<a href="http://link-url">/</a>.

When I hear the sentence “it can be either a Foo, a Bar or a Baz”, I take this as a cue to consider Discriminated Unions. The specific topic of html and markdown also brought back memories of a talk on Domain Specific Languages with F# by Tomas Petricek, which inspired me to try the following:

type Block =

| RawText of string

| Link of string * string // txt, url

| Image of string * string // alt, url

type Language =

| CSharp

| FSharp

| VB

| Other

type Content =

| Paragraph of Block list

| Header of string

| Code of Language * string

| Problem of string

This could of course be improved upon, but, once again, this is good enough, and represents fairly cleanly in code what I described before: the Content of a post can be a simple Header, a Code section, a Paragraph, which itself is a list of blocks (raw text, link or image) - or a Problem if we encounter something malformed.

All that’s left to do is to parse a post, in two passes: break it down first in a list of Content blocks, and then break down each Paragraph further into a list of Blocks.

Let’s start with the first pass, and ignore images and links for the moment. This is roughly what I started with:

let (|BlockBetween|_|) (openToken:string,closeToken:string) (txt:string) =

if txt.Length = 0

then None

elif txt.StartsWith openToken

then

let endAt = txt.IndexOf closeToken

let block = txt.Substring(0, endAt + closeToken.Length)

let rest = txt.Substring(endAt + closeToken.Length)

Some(block,rest)

else None

What this Active Pattern allows me to do is to pass a pair of tokens/delimiters, such as <h2> and </h2>, and apply the pattern to a string, to extract out a matching string, and the rest of the text, like this:

match "<h2>This is a header</h2>and this is more stuff" with

| BlockBetween ("<h2>","</h2>") (content,rest) -> Some(content,rest)

| _ -> None

… which produces the following result:

val it : (string * string) option =

Some ("<h2>This is a header</h2>", "and this is more stuff")

All I have to do now is to recursively walk down the document, and progressively process the post contents, until there is nothing left to do, along these lines:

let paragraphTokens = ("<p>","</p>")

let codeTokens = ("<pre ","</pre>")

let headerTokens = ("<h2>","</h2>")

let rec pageComponents acc (txt:string) =

match txt with

| BlockBetween paragraphTokens (block,rest) ->

let blocks = parseParagraph block

pageComponents ((Paragraph blocks) :: acc) rest

| BlockBetween codeTokens (block,rest) ->

let code = parseCode block

pageComponents (code :: acc) rest

| BlockBetween headerTokens (block,rest) ->

let header = parseHeader block

pageComponents (header :: acc) rest

| Malformed ["<p>";"<pre ";"<h2>"] (block,rest) ->

pageComponents ((Problem block) :: acc) rest

| _ -> acc |> List.rev

I’ll skip on the details (ask me in the comments if you want to know more); basically, we try to recognize either a paragraph, code, headers, or problematic blocks, apply the appropriate parser (parseParagraph for a paragraph, parseCode for code, etc…) to it (more on that in a second), append the result to a list and move to the remaining chunk of text until there is nothing left to do. At that point, we have converted a raw block of text in a list of well-defined Content.

Parsing stuff

I confess that when I began this, I hadn’t fully thought through how I would go about extracting information from images or links. When I hit that point, it quickly became apparent that my cheap BlockBetween approach was not going to cut it. Situations such as an image within a link within a paragraph quickly become very nasty. I briefly contemplated Regex - also not a great idea.

And then I remembered that fsharp.Data has an Html parser. Suddenly, life was good again.

This allowed me to do things along these lines:

#r "packages/fsharp.data/lib/net40/fsharp.data.dll"

open FSharp.Data

let parseHeader (txt:string) =

HtmlNode.Parse(txt)

|> List.head

|> HtmlNode.innerText

|> Header

We pass a string (expected to be a well-formed <h2> header) to HtmlNode.Parse, which returns a list of HtmlNodes; we take the first one (the head), grab its innerText, and construct a Header (one of the 4 cases of Content).

For headers, the benefits are marginal. However, when dealing with links, this begins to pay off:

let parseLink (node:HtmlNode) =

let imgs = node.Descendants ["img"]

if (Seq.isEmpty imgs)

then

let txt = node.InnerText ()

let url = node.AttributeValue("href")

Link(txt,url)

else

let img = imgs |> Seq.head

let txt = img.AttributeValue("alt")

let url = img.AttributeValue("src")

Image(txt,url)

In this case, we search inside an HtmlNode for potential images (descendants marked img); if there isn’t one, this is a pure link, and we grab the href attribute value, and construct a Link; otherwise, this is an image wrapped in a link, and we retrieve the alt and src attributes to form an Image.

I won’t go into more detail here. Some of the code is pretty ugly, and I am probably not using that parser in the best way possible - the main goal here was to quickly get something that was mostly working. My hope is to give you enough of a sense for what this parser does, so that if you encounter a similar problem, you’ll go check it out, but read the awesome documentation instead of relying on my horrendous, hacky code :)

Anyways - at that stage, conveniently ignoring a couple of details, we are about done. Once the raw html content has been converted into a list of Content, all we need is to convert each of them into its markdown representation. As a quick example, a Block can be either raw text, a link, or an image - all it takes is a bit of pattern matching to spit out a string:

let blockWriter (block:Block) =

match block with

| RawText(txt) -> txt

| Link(txt,url) -> sprintf "[%s](%s)" txt url

| Image (alt, url) -> sprintf "" alt url

Using the same idea at the Content level with a contentWriter function, we just have to take the raw html content, break it into a list of Content using our pageComponents function, apply a List.map contentWriter to convert everything to markdown string, concatenate, et voila! Most of the time, we have a well-formed markdown string, which we can now inject as content in our post template.

Conclusion

This is as far as I’ll go on this today. I obviously used a bit of hand-waving here and there, but hope that the main ideas are clear enough to be of some use. What I left out is so specific to my blog, that I doubt it would be directly applicable anywhere else (or so hacky that I would be ashamed to make it public…). If you want to know more, just ask in the comments!

One reason I thought the experience worth sharing is that it shows F# in action, solving an extremely banal, practical problem. F# is too often described as a language suitable to tackle specialized technical problems (finance, machine learning, scientific computing…) - which is absolutely correct, but entirely misses the fact that it is also an incredibly productive scripting language to get boring stuff done. All it took me was a lazy weekend afternoon to write a quick script pulling data out of SQL, downloading images, and writing a DSL and parser converting html documents into markdown files. Nothing fancy about any of this! I am sure you could be equally productive here with Python or PowerShell, but, at the same time, F# is rarely mentioned as a “glue” scripting languages for rapid prototyping or automation, whereas, in my opinion, it is one area where the language really shines.

Incidentally, this also means that I am done porting over my blog. At some point in the near future, once I have given it a once-over, I will retire the old one - and will exclusively post here from now on, on a true, hand-crafted hipster blog!

@hmemcpy no magic plugin for me, had to parse/convert everything to markdown myself. True artisanal, hand-crafted hipster blog :)

— Mathias Brandewinder (@brandewinder) August 15, 2016