Gini, Pareto and fairness

16 Sep 2008Macroeconomics and public policy have never been my forte in economics, which is probably why I did not come across the Gini coefficient until now. In a nutshell, the Gini coefficient is a clever way to measure inequalities of distribution in a population.

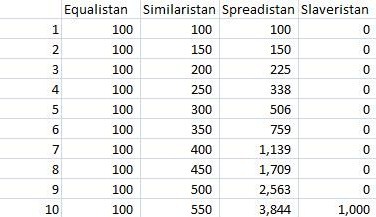

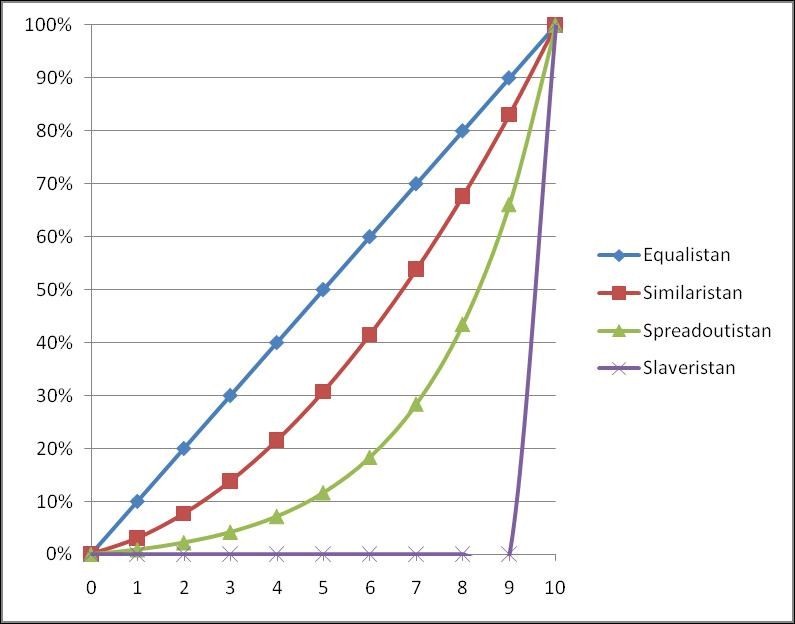

As an illustration, imagine 4 countries, each of them with 10 inhabitants. In Equalistan, everyone owns the same amount of $100, whereas in Slaveristan, one person owns everything, and the 9 others have nothing. In between, there are Similaristan and Spreadistan.

If you order the population by increasing wealth and plot out the cumulative % of the total wealth they own, you will get the so-called Lorentz curve. Equalistan and Slaveristan are the two extreme possible cases; any curve must fall between these two, and the further the curve is from Equalistan, the less equal the distribution. The Gini coefficient uses that idea, and measures the surface between the Equalistan curve and your curve; normalizing to obtain 100% for the Slaveristan case, and any population will have an index between 0% (perfectly equal) and 100% (absolutely unequal).

I came across the Gini coefficient through this post, which discusses its possible use to measure project risk. If the project’s success relied heavily on the contribution of few team members, the Gini index would capture the degree of concentration of that risk. I thought this was an interesting idea; the post provides an illustration, and shows (surprise!) that open-source software development projects usually rely on a few core contributors, and a multitude of lightweight, occasional helpers.

So what?

Imagine now that you calculated your Gini coefficient; what should you do next? What strikes me is that you can’t really use it beyond that. It provides a great description, but no clear path for improvement. Or, more precisely, the underlying solution is obvious - make everything equal - and it’s obviously not a great one.

This somehow reminded me of another concept from economics, the Pareto criterion. They both focus on distribution, but with a very different perspective. In a nutshell, the Pareto criterion considers how resources are distributed between individuals, and defines a situation to be Pareto-optimal if nobody’s situation can be improved without someone else’s becoming worse. Conversely, if a situation is not Pareto optimal, there is a way to reshuffle resources so that nobody is worse off, and at least someone gains.

In a sense, the Gini criterion is the anti-Pareto. A common criticism of Pareto optimality is that it has really nothing to do with fairness. If you think about it, the Pareto criterion hinges on a unanimity principle: if only one person loses in a re-distribution, it is not Pareto optimal. This could be seen as protecting individual’s right, but this is also totally independent from how the overall wealth is distributed. The classic illustration is to consider Slaveristan again; it is a very unfair situation, where one person has the entire wealth, and yet, it is Pareto optimal: reducing his wealth by any amount will reduce his well-being. By contrast, the Gini solution to the problem is to redistribute the resources equally, which is most likely going to make some happy, and some less.

Gini and Pareto are the two sides of the same question, asked from opposing angles. The Pareto criterion asks whether there is an unobtrusive way to improve everyone’s situation; which, if the initial situation is very unbalanced, will not improve much the situation of individuals at a disadvantage. By contrast, the Gini index considers an ideal world where everyone is equal, as a yardstick for evaluation, and ignores the sacrifices it may require from the individuals who are currently at an advantage.