Create an Excel 2007 VSTO add-in: display open worksheets in a TreeView

08 Mar 2010Excel VSTO Add-In Series

- Getting Started

- Custom Task Pane

- Ribbon

- WPF Control

- Tree View

- Excel Events

- Part 1 Wrap

- Go To Cell

- Read Worksheets

- Display Differences

- Msi Installer

- Code on GitHub

The shell of our control is ready – today we will fill the TreeView with all the open workbooks and worksheets. We will use a common design pattern in WPF: we will create objects that act as intermediary between the user interface and the domain objects. This approach is know as MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) in WPF, and is a variation on the classic Model-View-Presenter pattern – the main difference being that MVVM relies heavily on the data binding capabilities of WPF.

As usual, Josh Smith has some great material on how to use the WPF TreeView, which is highly recommended reading – and was a life-saver in figuring out how things work.

In a first step, we will fill in the TreeView with fake data, and once the UI “works”, we will hook up the objects to retrieve real data from Excel.

To quote Josh Smith, “the WinForms TreeView control is not really providing a “view” of a tree: it is the tree”, whereas “the TreeView in our WPF programs to literally provide a view of a tree”, to which we want to bind. In our case, the tree we want to represent is that Excel has a collection of Workbook objects, which each has a collection of Worksheet objects. Let’s build that structure.

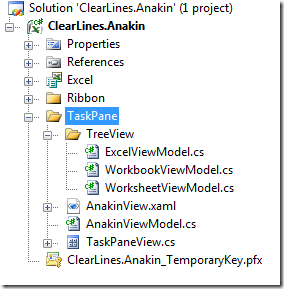

Let’s add a folder “TreeView” inside our existing TaskPane folder, and create 3 public classes: ExcelViewModel, WorkbookViewModel and WorksheetViewModel.

The ExcelViewModel will expose an ObservableCollection of its WorkbookViewModel(s), which will provide the View with information on how to display each workbook. We will temporarily add a few “fake” workbooks to the ExcelViewModel:

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

public class ExcelViewModel

{

private ObservableCollection<WorkbookViewModel> workbookViewModels;

internal ExcelViewModel()

{

this.workbookViewModels = new ObservableCollection<WorkbookViewModel>();

var fakeWorkbookViewModel1 = new WorkbookViewModel();

var fakeWorkbookViewModel2 = new WorkbookViewModel();

this.workbookViewModels.Add(fakeWorkbookViewModel1);

this.workbookViewModels.Add(fakeWorkbookViewModel2);

}

public ObservableCollection<WorkbookViewModel> Workbooks

{

get

{

return this.workbookViewModels;

}

}

}

Let’s do the same for the WorkbookViewModel, and add a Property Name, which will temporarily return a fake value “My Workbook”:

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

public class WorkbookViewModel

{

private ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel> worksheetViewModels;

internal WorkbookViewModel()

{

this.worksheetViewModels = new ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel>();

var fakeWorksheetViewModel1 = new WorksheetViewModel();

var fakeWorksheetViewModel2 = new WorksheetViewModel();

this.worksheetViewModels.Add(fakeWorksheetViewModel1);

this.worksheetViewModels.Add(fakeWorksheetViewModel2);

}

public ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel> Worksheets

{

get

{

return this.worksheetViewModels;

}

}

public string Name

{

get

{

return "My Workbook";

}

}

}

And finally, the WorksheetViewModel simply exposes a temporary fake name:

public class WorksheetViewModel

{

public string Name

{

get

{

return "My Worksheet";

}

}

}

Now that the tree structure is in place, let’s hook it up to the control. We will expose the add-in functionality to the AnakinView user control through one class, the AnakinViewModel; it will handle the actions received from the user through the AnakinView, and transform data coming from Excel in a format suitable for user interface consumption. Let’s create that class, in the same place as the AnakinViewControl, so that our project looks like this:

We need to associate the AnakinView with its view model; WPF controls have a property, DataContext, which enables this association: any object can be passed as DataContext to the control, and the control will do its best to bind to the object properties.

We will do so in the Add-In startup method, so that as soon as the control is created, it is supplied with an access to the Add-In functionality. First, we need to provide access to the AnakinView control: it is currently not visible through the TaskPaneView, because the field which was created when we added the element host and the user control are private. Let’s add an internal property to the TaskPaneView: right-click on the TaskPaneView.cs file, select “show code”, and edit the code to the following:

public partial class TaskPaneView : UserControl

{

public TaskPaneView()

{

InitializeComponent();

}

internal AnakinView AnakinView

{

get

{

return this.anakinView1;

}

}

}

Now that we have access to the WPF control, let’s set the DataContext in the startup method, like this:

private void ThisAddIn_Startup(object sender, System.EventArgs e)

{

var taskPaneView = new TaskPaneView();

this.taskPane = this.CustomTaskPanes.Add(taskPaneView, "Anakin");

this.taskPane.Visible = false;

var anakinViewModel = new AnakinViewModel();

var anakinView = taskPaneView.AnakinView;

anakinView.DataContext = anakinViewModel;

}

At that point, we are largely done; what remains to do is to tell the TreeView in the AnakinView user control where it should find data in the DataContext, that is, the AnakinViewModel. The tree view is, more or less, a list of list of list (etc…); for the control to be able to bind to the ViewModel, we need to tell it where the root element is, and where the “next” list is located. Let’s start by the root, the ExcelViewModel. First, the AnakinViewModel needs to provide access to the ExcelViewModel, so let’s add the following code:

using ClearLines.Anakin.TaskPane.TreeView;

public class AnakinViewModel

{

private ExcelViewModel excelViewModel;

public ExcelViewModel ExcelViewModel

{

get

{

if (this.excelViewModel == null)

{

this.excelViewModel = new ExcelViewModel();

}

return this.excelViewModel;

}

}

}

We are using lazy-loading here: the AnakinViewModel itself creates its ExcelViewModel “on-demand”, when it is requested by the property.

Next, we can start filling the tree, by telling it that it should look for the root element of the tree in the ExcelViewModel property of the AnakinViewModel, and how it should render the WorkbookViewModel(s) it will find there. Let’s change the xaml code of the AnakinView.xaml to the following:

<UserControl x:Class="ClearLines.Anakin.TaskPane.AnakinView"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

xmlns:TreeView="clr-namespace:ClearLines.Anakin.TaskPane.TreeView">

<StackPanel Margin="5">

<Button Width="75" Height="30"

Margin="0,0,0,5"

HorizontalAlignment="Left">

Refresh

</Button>

<TreeView ItemsSource="{Binding Path=ExcelViewModel.Workbooks}" Height="200">

<TreeView.Resources>

<HierarchicalDataTemplate

DataType="{x:Type TreeView:WorkbookViewModel}">

<StackPanel Margin="0,0,0,3">

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Name}"/>

</StackPanel>

</HierarchicalDataTemplate>

</TreeView.Resources>

</TreeView>

</StackPanel>

</UserControl>

The main changes to note are:

- We added ItemsSource=”{Binding Path=ExcelViewModel.Workbooks}” in the opening TreeView tag. This instructs the TreeView that the source of data is to be found at the path ExcelViewModel.Workbooks, in the DataContext.

- The section TreeView.Resources provides the TreeView with instructions on the way the data is organized, and how it should render elements. The HierarchicalDataTemplate declares that when items of type WorkbookViewModel are encountered, they should be rendered using a StackPanel, and display in a TextBlock the text that is found in the Name property.

- The line xmlns:TreeView=”clr-namespace:ClearLines.Anakin.TaskPane.TreeView”, which has been added at the top of the control, is the equivalent of a using statement, and points to the namespace where the WorkbookViewModel resides.

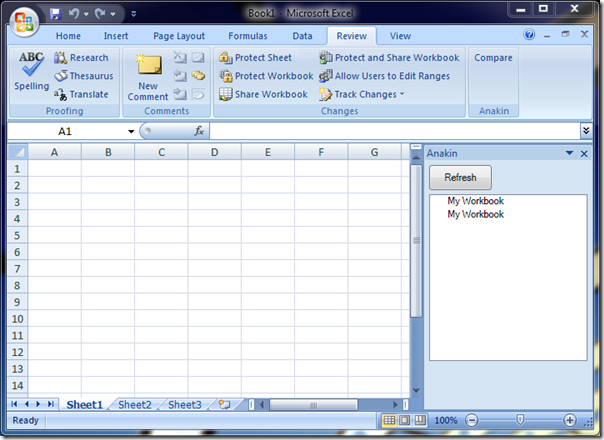

If you debug the add-in at that point, you should see the following:

Nothing amazing yet, but it proves that the binding does take place: the TreeView now shows our two fake workbooks names. Let’s add the binding to the worksheets, by adding another HierarchicalDataTemplate:

<TreeView.Resources>

<HierarchicalDataTemplate

DataType="{x:Type TreeView:WorkbookViewModel}"

ItemsSource="{Binding Worksheets}">

<StackPanel Margin="0,0,0,3">

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Name}"/>

</StackPanel>

</HierarchicalDataTemplate>

<HierarchicalDataTemplate

DataType="{x:Type TreeView:WorksheetViewModel}">

<StackPanel Margin="0,0,0,3">

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Name}"/>

</StackPanel>

</HierarchicalDataTemplate>

</TreeView.Resources>

The second template pretty much replicates what we did for the workbooks, and simply tells the control how to render a worksheet. Note that in the first template, the following line has been added: ItemsSource="{Binding Worksheets}". This announces to the control that when displaying a Workbook, it should look for a “nested”, hierarchical list of items, called Worksheets – which will be rendered using the second template.

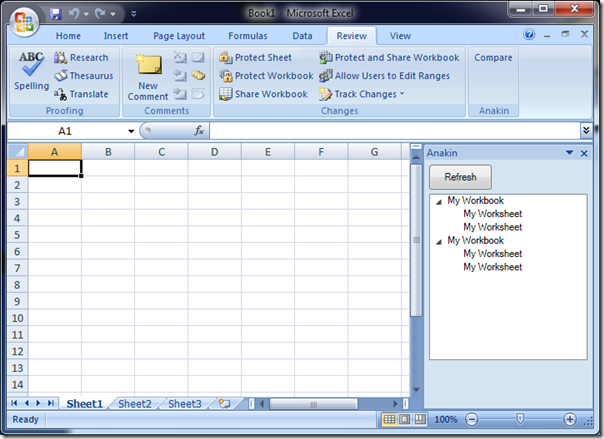

Hit F5, and now we see a complete tree:

The bindings work – now we just have to hook up the various View Models so that instead of fake data, they display “real” data coming from Excel. Piece of cake. Let’s start by feeding real workbooks into the WorkbookViewModel: we add a reference/alias to Excel, change the constructor, which now expects a workbook, and re-pipe the Name property to retrieve the name of the actual workbook.

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using Excel = Microsoft.Office.Interop.Excel;

public class WorkbookViewModel

{

private ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel> worksheetViewModels;

private readonly Excel.Workbook workbook;

internal WorkbookViewModel(Excel.Workbook workbook)

{

this.worksheetViewModels = new ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel>();

this.workbook = workbook;

var fakeWorksheetViewModel1 = new WorksheetViewModel();

var fakeWorksheetViewModel2 = new WorksheetViewModel();

this.worksheetViewModels.Add(fakeWorksheetViewModel1);

this.worksheetViewModels.Add(fakeWorksheetViewModel2);

}

public ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel> Worksheets

{

get

{

return this.worksheetViewModels;

}

}

public string Name

{

get

{

return workbook.Name;

}

}

}

Now we need to modify the ExcelViewModel. Instead of creating fake workbooks, we will call a method, PopulateWorkbooks, which accesses Excel through the Add-In, iterates through all open workbooks, and creates a WorkbookViewModel for each:

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using Excel = Microsoft.Office.Interop.Excel;

public class ExcelViewModel

{

private ObservableCollection<WorkbookViewModel> workbookViewModels;

internal ExcelViewModel()

{

this.workbookViewModels = new ObservableCollection<WorkbookViewModel>();

this.PopulateWorkbooks();

}

public ObservableCollection<WorkbookViewModel> Workbooks

{

get

{

return this.workbookViewModels;

}

}

private void PopulateWorkbooks()

{

var excel = Globals.ThisAddIn.Application;

var workbooks = excel.Workbooks;

foreach (var workbook in workbooks)

{

var book = workbook as Excel.Workbook;

if (book != null)

{

var workbookViewModel = new WorkbookViewModel(book);

this.workbookViewModels.Add(workbookViewModel);

}

}

}

}

If you run the Add-In at that point, you’ll see that instead of our 2 fake workbooks, only one Workbook appears, with the proper name – but it is still filled with fake worksheets. Let’s address that in the same fashion, by first modifying the WorksheetViewModel, which will use a real Worksheet:

using Excel = Microsoft.Office.Interop.Excel;

public class WorksheetViewModel

{

private Excel.Worksheet worksheet;

public WorksheetViewModel(Excel.Worksheet worksheet)

{

this.worksheet = worksheet;

}

public string Name

{

get

{

return this.worksheet.Name;

}

}

}

… and update the WorkbookViewModel, to iterate over its worksheets and create one WorksheetViewModel for each:

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using Excel = Microsoft.Office.Interop.Excel;

public class WorkbookViewModel

{

private ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel> worksheetViewModels;

private readonly Excel.Workbook workbook;

internal WorkbookViewModel(Excel.Workbook workbook)

{

this.worksheetViewModels = new ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel>();

this.workbook = workbook;

var worksheets = workbook.Worksheets;

foreach (var sheet in worksheets)

{

var worksheet = sheet as Excel.Worksheet;

if (worksheet != null)

{

var worksheetViewModel = new WorksheetViewModel(worksheet);

this.worksheetViewModels.Add(worksheetViewModel);

}

}

}

public ObservableCollection<WorksheetViewModel> Worksheets

{

get

{

return this.worksheetViewModels;

}

}

public string Name

{

get

{

return workbook.Name;

}

}

}

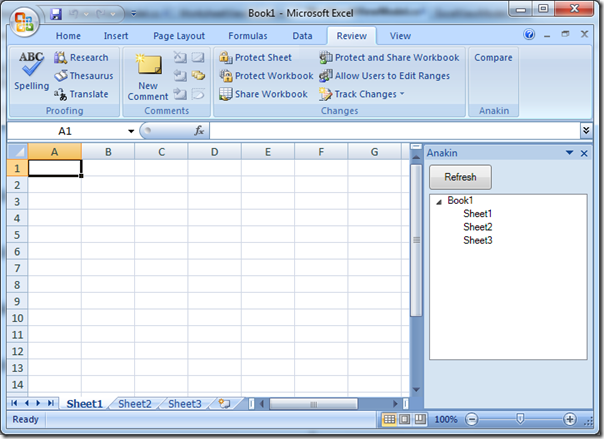

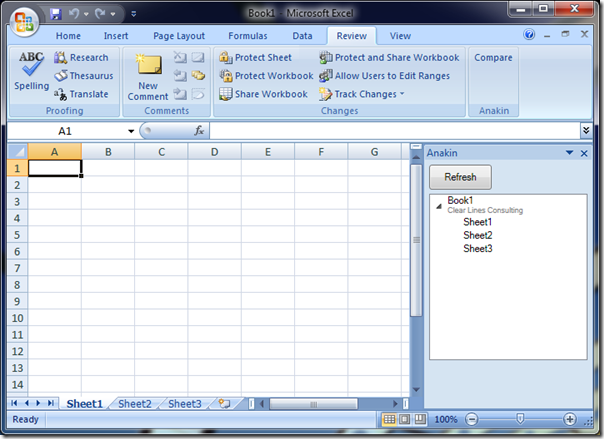

And that’s it. If you hit F5 right now, you will see the following: the TreeView displays a Workbook, with the proper Worksheet names:

This may look like a lot of work, just to populate a simple tree. On the other hand, now that the artillery is in place, we can customize the way items are rendered in the tree, without much extra work. For instance, let’s add the name of the Author of the workbook discreetly below the name. To do this, we need to add that property to the WorkbookViewModel, like this:

public string Author

{

get

{

return this.workbook.Author;

}

}

And let’s alter the HierarchicalDataTemplate slightly:

<HierarchicalDataTemplate

DataType="{x:Type TreeView:WorkbookViewModel}"

ItemsSource="{Binding Worksheets}">

<StackPanel Margin="0,0,0,3">

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Name}"/>

<TextBlock Text="{Binding Author}" FontSize="9" Foreground="Gray"/>

</StackPanel>

</HierarchicalDataTemplate>

The TreeView now shows the following:

The point here is that while creating a ViewModel for different types of entities creates some overhead, once they are broken up that way, it is fairly easy to display each of them in a specific way – and customizing the way they are rendered is straightforward.

We are almost done with the TreeView at that point. The two issues we still have to cope with are that right now, it is populated with the default workbook that is opened when Excel launches, and we need to refresh the contents when the “Refresh” button is clicked. We also need to convey to the ViewModel which worksheet is currently selected – that is, after all, the whole point of that part of the control. This is what we will handle in our next installment!

As usual, I welcome comments, questions and criticisms from my readers!

I also realize that at that point in time, there is enough code that it is becoming worthwhile to post it, I will do so very shortly.