Supercharge Excel functions with ExcelDNA and .Net parallelism

13 Jun 2010In my last post I explored how ExcelDNA can be used to write high-performance UDFs for Excel, calling .Net code without the overhead of VSTO. Using .Net instead of VBA for intensive computations already yields a nice improvement. Still, I regretted that ExcelDNA supports .Net up to 3.5 only, which puts the Task Parallel Library off limits – and is too bad because the TPL is just totally awesome to leverage the power of multi-cores.

As it turned out, this isn’t totally correct. Govert Van Drimmelen (the man behind ExcelDNA) and Jon Skeet (the Chuck Norris of .Net) pointed that while the Task Parallel Library is a .Net 4.0 library, the Reactive Extensions for .Net 3.5 contains an unsupported 3.5 version of the TPL – which means that it should be possible to get parallelism to work with ExcelDNA.

This isn’t a pressing need of mine, so I thought I would leave that alone, and wait for the 4.0 version of ExcelDNA. Yeah right. Between my natural curiosity, Ross McLean’s comment (have fun at the Excel UK Dev Conference!), and the fact that I really want to know if I could get the Walkenbach test to run under 1 second, without too much of an effort, I had to check. And the good news is, yep, it works.

Last time we saw how to turn an average PC into a top-notch performer; let’s see how we can inject some parallelism to get a smoking hot calculation engine.

So here is what I had to do to get my CPUs to crank calculations like there is no tomorrow:

- Download the Rx Extensions for .Net 3.5 SP1 (or get it from the project page here and install it on your development machine

- Look into C:\Program Files\Microsoft Cloud Programmability\Reactive Extensions\v1.0.2563.0\Net35, where you should find, among other things, a dll named System.Threading.dll

- In your Visual Studio project, create a folder (I named mine Libs), drop in a copy of the System.Threading dll, and add the dll as an “existing item” In your Visual Studio project, right-click on References > Add Reference > Browse, and navigate to the folder where the you dropped the dll.

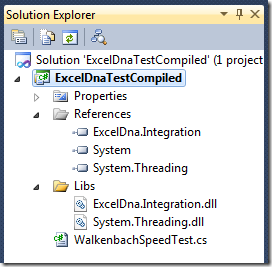

At that point your project should look more or less like this:

Now let’s modify a bit the code I wrote last time, and extract the simulation into a separate method, for clarity:

private static int RunSimulation(int runs)

{

var position = 0;

var random = new Random(Guid.NewGuid().GetHashCode());

for (var run = 0; run < runs; run++)

{

if (random.Next(0, 2) == 0)

{

position++;

}

else

{

position--;

}

}

return position;

}

Once the simulation is factored out, the non-parallel version of the random walk looks like this:

public static string RandomWalk()

{

var stopwatch = new Stopwatch();

stopwatch.Start();

var position = RunSimulation(100000000);

stopwatch.Stop();

var elapsed = (double)stopwatch.ElapsedMilliseconds / 1000d;

return "Position: " + position.ToString() + ", Seconds: " + elapsed.ToString();

}

Looking at the RunSimulation method, it is clear that we can run things in parallel without harm, because there is no common state: rather than run one 100,000,000 steps random walk simulation and recording the final position, we might as well run 100 smaller 1,000,000 random walks, and compute the sum of their final positions.

After adding a using System.Threading statement at the top of the class, here is how my parallel code looks like:

public static string ParallelRandomWalk()

{

var stopwatch = new Stopwatch();

stopwatch.Start();

var bag = new ConcurrentBag<int>();

Parallel.For(0, 100, i =>

{

var position = RunSimulation(1000000);

bag.Add(position);

});

stopwatch.Stop();

var total = 0;

foreach (var i in bag)

{

total += i;

}

var elapsed = (double)stopwatch.ElapsedMilliseconds / 1000d;

return "Position: " + total.ToString() + ", Seconds: " + elapsed.ToString();

}

Instead of running one single loop, I used the Parallel.For construct, which essentially says “for i = 0 to 99, run a simulation and add the result to the bag – and please try to run these in parallel the best you can, given the computer you are running on”. Once the 100 simulations terminated, we sum the values of the bag, and return that. The reason I am using a ConcurrentBag here is to make sure that the result of each simulation is recorded properly. We could have multiple threads trying to record results at the same time, with the risk of data being dropped – a problem concurrent collections like the ConcurrentBag are designed to address.

Disclaimer: I began working with the Task Parallel Library only fairly recently, and don’t claim expertise there. If you see any obvious ways to make this better, I am all ears!

We are almost done now. Proceed like in step 3 of the ExcelDNA getting started tutorial, but in the location where your dll is located, also drop a copy of the System.Threading.dll.

So what did we buy here? Running this on the same dual-core laptop, I saw a drop from around 5.9 seconds using .Net with no parallelism, to about 3.4 seconds. Not bad – another 40% + gained, and we are now smoking the fastest computer using VBA in John Walkenbach’s sample.

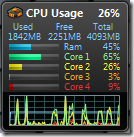

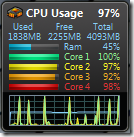

Can we do better? Probably not on this laptop, but on a better machine, with more cores, sure. Can we get this under 1 seconds? I tried this on my quad-core workstation, and got it down to an average around 1.35 seconds. When I run both versions, here is what I see:

The left picture shows the initial version, using 26% of the computing power available, whereas the right one displays what is going on with the parallel version, offloading simulations on every available core, and using 97% of the capacity we have at hand.

What’s the conclusion here? Obviously, that in some cases, like intensive computations, using a tool like ExcelDNA can help create user-defined functions that are considerably faster than their VBA equivalent, by calling .Net dlls, at limited cost – and that if there is room for parallelism in the computation, even more gain is possible, at the cost of slightly more complex code, using the task parallel library.

A word of caution, though: parallel computing comes with its own challenges. I mentioned the issue of concurrency we resolved by using the ConcurrentBag. As another example of potential problems, you may have noted that while my previous example simply used var random = new Random(), the code now instantiates a Random for each parallel loop, with var random = new Random(Guid.NewGuid().GetHashCode(). There are two things worth noting here. First, I used one instance of Random per loop, because Random is not thread-safe: if we used the same Random for all loops, each of them would call it concurrently, and this results in highly non-random results. Second, I seeded each random with Guid.NewGuid().GetHashCode(): the reason for this is that if I simply called new Random(), the seed of the random number generator is based on the system timer, and if two Randoms are created too close in time, they will have the same seed, and produce the same “random” sequence. For instance, if you try out the following code, you will observe that the output is again not very random-looking, producing long sequences of 0s or 1s:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

var random = new Random();

Console.WriteLine(random.Next(0, 2));

}

Console.ReadKey();

}

So… enjoy parallelism, but parallelize responsibly!