First steps with the Microsoft Solver Foundation

16 Jul 2011While most of my posts tend to focus on software development, my background is in optimization. Unfortunately, I don’t get to use these two skillsets together too often, because most projects require fairly basic modeling, and because the tools they require do not always integrate well together.

Luckily, the project I am currently working on involved performing some optimization, from within a .NET application, which gave me an opportunity to investigate the Microsoft Solver Foundation, which comes with a free solver and provides a framework for leveraging existing commercial solvers.

What is a solver? In a nutshell, it is an algorithm designed to identify optimal input values to maximize a function, while satisfying constraints. Certain classes of problems can be solved very efficiently using known algorithms, while others require the use of heuristics – but in general, if you find yourself asking “what is the best combination of values for this situation”, chances are, a solver is the tool you should be using.

Rather than go into theory, let’s look at an illustration, which will hopefully give you a sense for what the Microsoft Solver Foundation can do for you, and how you can leverage it in your .NET applications.

The problem: cheap imports from Gadgetistan

Imagine the following situation. You are an enterprising individual, and realize that there is good money to be made by importing goods from the Republic of Gadgetistan, the neighboring country. You break the piggybank, invest in an old truck, drive over there and get ready to buy a truckload of the local specialties, Widgets, Sprockets and Gizmos.

The truck didn’t come cheap, so you have only 200 Rublars (the official currenty of Gadgetistan) left in your wallet – this is your Budget Constraint.

The truck user manual is very clear – the Capacity of your truck is 500 Kilograms. One pound more, and your wonderful truck could collapse in a sad heap of scrap metal. This is your Capacity Constraint.

A bit of market research yielded the following information about the main product: the buying Cost, the reselling Price, and the Weight for a unit of each of the main goods from Gadgetistan.

| **Cost (Rublars)** | **Price (Rublars)** | **Weight (Kgs) --- | --- | --- | --- **Widget** | 10 | 30 | 50 **Sprocket** | 15 | 30 | 20 **Gizmo** | 25 | 60 | 80

Your problem at that point is simple: how many units of each product should you carry in your truck, to make the most of your trip?

Finding a solution with the Microsoft Solver Foundation

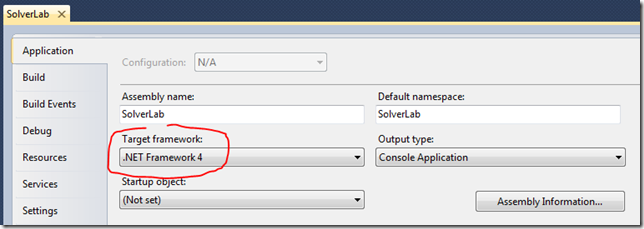

We will solve the problem with a simple Console application. First, let’s create a Console project, SolverLab, targeting the .NET 4.0 framework, and setting the target to the full .NET 4.0 profile (and not the client profile).

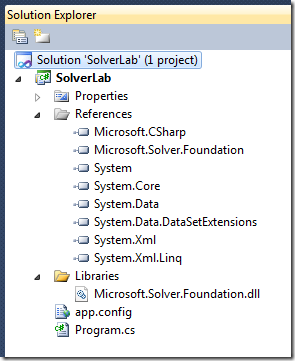

Next, go to the Microsoft Solver Foundation page, download the Solver Foundation v3.0 – DLL only, add the corresponding dll to the project, and add a reference to the project:

We are now set to write our optimization program.

Our first step is to define what input variables the Solver is trying to optimize; in optimization speak, this is called “Decision Variables”. In our example, we have 3 decisions: the quantity or Widgets, Sprockets and Gizmos – which we’ll rename here to A, B and C, for the sake of conciseness. This is how this looks in code (which will require adding using Microsoft.SolverFoundation.Services; in the code file):

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var solver = SolverContext.GetContext();

var model = solver.CreateModel();

var decisionA = new Decision(Domain.IntegerNonnegative, "QuantA");

var decisionB = new Decision(Domain.IntegerNonnegative, "QuantB");

var decisionC = new Decision(Domain.IntegerNonnegative, "QuantC");

model.AddDecision(decisionA);

model.AddDecision(decisionB);

model.AddDecision(decisionC);

We instantiate a solver, create a model, and declare 3 decision variables, which we add to the model. Note that for each decision, we define a Domain: the domain specifies the “range” that is valid for the parameter. In our case, we want the answer to be a positive integer (we cannot buy half-sprockets). There are other alternatives, such as Real Numbers or Booleans, Nonnegative or unconstrained.

Next, we need to define what we are trying to optimize – the Goal, also often called the Objective function. Here we want to maximize our profit, that is, for each product, units x (price – cost), which we express in code as:

var costA = 10d;

var costB = 15d;

var costC = 25d;

var priceA = 30d;

var priceB = 30d;

var priceC = 60d;

model.AddGoal("Goal", GoalKind.Maximize,

(priceA - costA) * decisionA +

(priceB - costB) * decisionB +

(priceC - costC) * decisionC);

We create variables for the cost and price of each product, and simply add a Goal to the model, specifying what we are trying to do (Maximize), and directly type in the expression for our goal. In general, the Solver works with Terms (more on this in our next post), but it also accepts strings which will be parsed as OML expressions. I found it to be very flexible in accepting human-readable, free-form strings, and making sense of them.

Finally, we need to add the two Constraints to the program, following a similar pattern to the Goal definition:

var budget = 200d;

model.AddConstraint("Budget",

costA * decisionA +

costB * decisionB +

costC * decisionC <= budget);

var weightA = 50d;

var weightB = 20d;

var weightC = 80d;

var capacity = 500d;

model.AddConstraint("Weight",

weightA * decisionA +

weightB * decisionB +

weightC * decisionC <= capacity);

And we are set – we can now let the solver work its magic, and search for 3 quantities which will give us the best profit, while being under budget and keeping our truck intact:

var solution = solver.Solve();

Console.WriteLine("A " + decisionA.GetDouble());

Console.WriteLine("B " + decisionB.GetDouble());

Console.WriteLine("C " + decisionC.GetDouble());

Console.ReadLine();

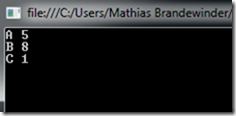

Calling solver.Solve() will resolve the current model, and set the Decisions to their optimal value (if such a value is found) – and when we run the program, the following solution shows up: 5 Widgets, 8 Sprockets and 1 Gizmo.

We can check that the constraints are satisfied:

Capacity: 5 x 50 + 8 x 20 + 1 x 80 = 490 <= 500

Budget: 5 x 10 + 8 x 15 + 1 x 25 = 195 <= 200

The Profit of our solution comes out to be 5 x (30 – 10) + 8 x (30 – 15) + 1 x (60 - 25) = 255. It’s certainly a nice margin – but how do we know we can’t do better?

In this situation, we could brute-force every possible combination, and check whether there is anything better. That would work out because it’s a small problem, but clearly wouldn’t be convenient with a larger problem. Fortunately, the Solution returned by the solver has a property, Quality, which provides some information about what to expect from the solution, as an enum: Optimal, Feasible, Unfeasible, Unknown, Unbounded…

var solution = solver.Solve();

Console.WriteLine(solution.Quality);

In this case, the solution happens to be Optimal, which means that it is guaranteed to be the best possible. Possibly, other solutions could be just as good, but no solution can be better. How the solver knows that would go beyond the scope of that post (the problem happens to fit a certain structure, for which a perfect solution can be derived); suffice it to say that if the solution has been found, it can be simply feasible – meaning that it is a solution, but cannot be guaranteed to be the best – or optimal, meaning that it is guaranteed to be the best possible.

That’s it for today! Hopefully, this brief introduction will have given you a taste of what a solver can do for you. Next time, we’ll dig deeper into how to achieve stronger integration with your .NET code, by creating optimization models dynamically, and solving problems that follow the same template for any arbitrary inputs.