Unconstrained continuous optimization with Bumblebee

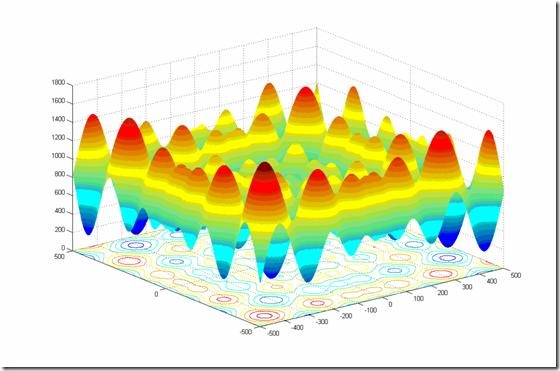

27 Jun 2012This months’ issue of MSDN Magazine has an interesting piece on evolutionary algorithms. The article applies a genetic algorithm to identify the minimum value of a “pathological” continuous function, the Schwefel function.

For X and Y values between –500 and 500, the “correct” answer is X and Y = 420.9687.

This function is designed to give fits to optimization algorithms. The issue here is that the function has numerous peaks and valleys. As a result, if the search strategy is to use some form of gradient approach, that is, from a starting point, follow the steepest descent until a minimum is reached, there is a big risk to end up in a place which is a local minimum: the algorithm gets stuck in a valley with no path downwards, but there are other, better solutions around, which can be reached only by “climbing out of the hole” and temporarily following a path which heads in the wrong direction.

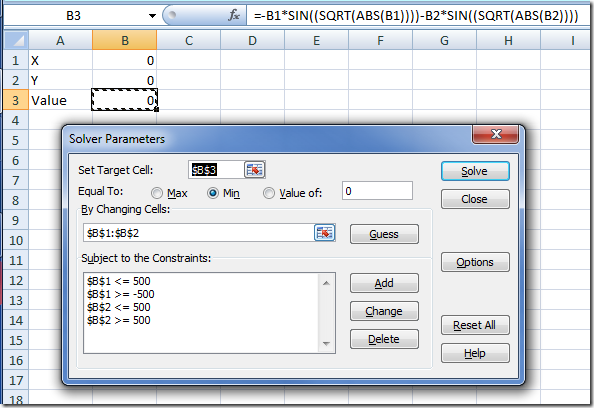

Out of curiosity, I checked how the Excel Solver would fare on this problem:

The result was an abject failure – not even close to the true solution.

I thought it would be interesting to see how Bumblebee, my Artificial Bee Colony framework, would perform. There are some general similarities between the underlying ideas behind the articles’ algorithm and Bumblebee, the main difference being that Bumblebee simply mutates individual solutions, and doesn’t create “crossover solutions”.

Let’s open Visual Studio, create an F# Console project, grab the NuGet package for Bumblebee – and start coding.

As usual, we need 4 elements to leverage Bumblebee – a Type of Solution, and 3 functions: a Generator, which returns a brand-new, random solution, a Mutator, which transforms a known solution into a new, similar solution, and an Evaluator, which evaluates a solution and returns a float, increasing with the quality of the solution.

In this case, the Solution type is fairly straightforward. We are looking for 2 floats x and y, so we’ll go for a Tuple. Similarly, the Evaluation is a given, it is the negative of the Schwefel function. The reason we go for the negative is that Bumblebee will try to maximize the Evaluation, so if we are looking for a minimum, we need to reverse the sign – because the Minimum of a function is the Maximum of its negative.

let schwefel x =

-x * Math.Sin(Math.Sqrt(Math.Abs(x)))

let evaluate (x, y) =

- schwefel (x) - schwefel (y)

The Generation function is also trivial – we’ll simply pick random pairs of floats in the [ –500.0; 500.0 ] interval:

let min = -500.0

let max = 500.0

let generate (rng: Random) = (

rng.NextDouble() * (max - min) + min,

rng.NextDouble() * (max - min) + min)

The Mutation function takes a tiny bit more of effort. The idea I followed is essentially the same as the one used in the article: given a solution defined by a pair of floats, randomly decide if any of the elements will be mutated, and if yes, add a random permutation to that element, scaled to the precision we want to achieve:

let precision = 0.00001

let rate = 0.5

let mutate (rng: Random) solution =

let (x, y) = solution

let x =

if rng.NextDouble() < rate

then x + precision * ((max - min) * rng.NextDouble() + min)

else x

let y =

if rng.NextDouble() < rate

then y + precision * ((max - min) * rng.NextDouble() + min)

else y

(x, y)

At that point, the stage is set – the problem is fully specified, and we can now pass it to Bumblebee. We wire our Console app the same way as usual, displaying the improvements in the Console as we find them (the complete code sample is at the bottom of the post).

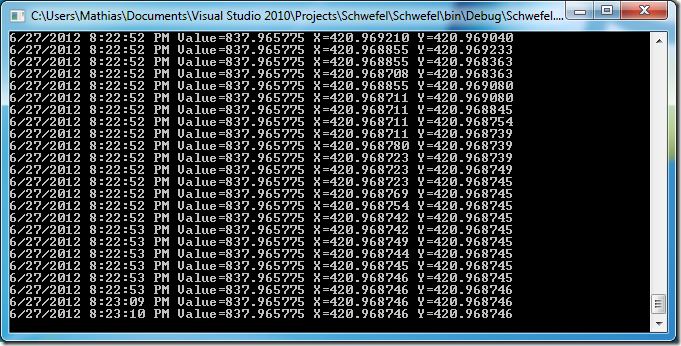

In a matter of seconds, Bumblebee identifies an excellent approximation for the true minimum around (420.9687; 420.9687). Awesome!

So does this mean that Bumblebee – or more generally randomized search algorithms – are the right way to go for unconstrained continuous optimization? I would certainly not say yes in general. “Classic” optimization techniques are great in non pathological cases, and, unlike randomized approaches, they provide results which are replicable and offer some guarantees on the quality of the result. At the same time, if the problem involves a large space search, and/or functions with multiple extrema, they are an interesting alternative. This was my first foray in continuous optimization using Bumblebee, and I was very pleasantly surprised by the result!

That’s it for today – the entire code sample is below, please let me know what you think in the comments.

open System

open ClearLines.Bumblebee

let main =

let schwefel x =

-x * Math.Sin(Math.Sqrt(Math.Abs(x)))

let evaluate (x, y) =

- schwefel (x) - schwefel (y)

let min = -500.0

let max = 500.0

let generate (rng: Random) = (

rng.NextDouble() * (max - min) + min,

rng.NextDouble() * (max - min) + min)

let precision = 0.00001

let rate = 0.5

let mutate (rng: Random) solution =

let (x, y) = solution

let x =

if rng.NextDouble() < rate

then x + precision * ((max - min) * rng.NextDouble() + min)

else x

let y =

if rng.NextDouble() < rate

then y + precision * ((max - min) * rng.NextDouble() + min)

else y

(x, y)

let problem = new Problem<(float * float)>(generate, mutate, evaluate)

let solver = new Solver<(float * float)>()

let displaySolution = fun (msg: SolutionMessage<(float * float)>) ->

Console.WriteLine("{0} Value={1:F6} X={2:F6} Y={3:F6}", msg.DateTime, msg.Quality, fst msg.Solution, snd msg.Solution)

solver.FoundSolution.Add displaySolution

Console.WriteLine("Starting at " + DateTime.Now.ToString())

solver.Search(problem) |> ignore

Console.ReadLine()