Simulating a simple Queue in F#

08 Jul 2012I recently spent some time thinking about code performance optimization problems, which led me to dust my old class notes on Queuing Theory. In general, Queuing studies the behavior of networks of Queues, where jobs arrive at various time intervals, and wait in line until they can be processed / served by a Node / Server, potentially propagating new Jobs going to other connected queues upon completion.

Side note: the picture above is not completely random. It depicts the Marsupilami, a fictional creature who is an expert in managing long tails, known in French as “Queues”>

The simplest case in Queues is known as the Single-Server Queue – a queue where all jobs wait in a single line, and are processed by a single server. Single queues are interesting in their own right, and can be found everywhere. They are also important, because they are the building blocks of Networks of Queues, and understanding what happens at a single Queue level helps understand how they work when connected together.

The question we’ll be looking at today is the following: given the characteristics of a Queue, what can we say about its performance over time? For instance, can we estimate how often the Queue will be busy? How many jobs will be backed up waiting for service on average? How large can the queue get? How long will it take, on average, to process an incoming job?

We’ll use a simple Monte-Carlo simulation model to approach these questions, and see whether the results we observe match the results predicted by theory.

What we are interested in is observing the state of the Queue over time. Two events drive the behavior of the queue:

- a new Job arrives in the queue to be processed, and either gets processed immediately by the server, or is placed at the end of the line,

- the server completes a Job, picks the next one in line if available and works on it until it’s done.

From this description, we can identify a few elements that are important in modeling the queue:

- whether the Server is Idle or Busy,

- whether Jobs are waiting in the Queue to be processed,

- how long it takes the Server to process a Job,

- how new Jobs arrive to the Queue over time

Modeling the Queue

Let’s get coding! We create a small F# script (Note: the complete code sample is available at the bottom of the post, as well as on FsSnip), and begin by defining a Discriminated Union type Status, which represents the state of the Server at time T:

type Status = Idle | Busy of DateTime * int

Our server can be in two states: Idle, or Busy, in which case we also need to know when it will be done with its current Job, and how many Jobs are waiting to be processed.

In order to model what is happening to the Queue, we’ll create a State record type:

type State =

{ Start: DateTime;

Status: Status;

NextIn: DateTime }

Start and Status should be self-explanatory – they represent the time when the Queue started being in that new State, and the Server Status. The reason for NextIn may not be as obvious - it represents the arrival time of the next Job. First, there is an underlying assumption here that there is ALWAYS a next job: we are modeling the Queue as a perpetual process, so that we can simulate it for as long as we want. Then, the reason for this approach is that it simplifies the determination of the transition of the Queue between states:

let next arrival processing state =

match state.Status with

| Idle ->

{ Start = state.NextIn;

NextIn = state.NextIn + arrival();

Status = Busy(state.NextIn + processing(), 0) }

| Busy(until, waiting) ->

match (state.NextIn <= until) with

| true ->

{ Start = state.NextIn;

NextIn = state.NextIn + arrival();

Status = Busy(until, waiting + 1) }

| false ->

match (waiting > 0) with

| true ->

{ Start = until;

Status = Busy(until + processing(), waiting - 1);

NextIn = state.NextIn }

| false ->

{ Start = until;

Status = Idle;

NextIn = state.NextIn }

This somewhat gnarly function is worth commenting a bit. Its purpose is to determine the next state the Queue will enter in, given its current state, and 2 functions, arrival and processing, which have the same signature:

val f : (unit -> TimeSpan)

Both these functions take no arguments, and return a TimeSpan, which represents respectively how much time will elapse between the latest arrival in the Queue and the next one (the inter-arrival time), and how much time the Server will take completing its next Job. This information is sufficient to derive the next state of the system:

-

If the Server is Idle, it will switch to Busy when the next Job arrives, and the arrival of next Job is schedule based on job inter-arrival time,

-

If the Server is Busy, two things can happen: either the next Job arrives before the Server completes its work, or not. If a new Job arrives first, it increases the number of Jobs waiting to be processed, and we schedule the next Arrival. If the Server finishes first, if no Job is waiting to be processed, it becomes Idle, and otherwise it begins processing the Job in front of the line.

We are now ready to run a Simulation.

let simulate startTime arr proc =

let nextIn = startTime + arr()

let state =

{ Start = startTime;

Status = Idle;

NextIn = nextIn }

Seq.unfold (fun st ->

Some(st, next arr proc st)) state

We initialize the Queue to begin at the specified start time, with a cold-start (Idle), and unfold an infinite sequence of States, which can go on if we please.

Running the Simulation

Let’s start with a Sanity check, and validate the behavior of a simple case, where Jobs arrive to the Queue every 10 seconds, and the Queue takes 5 seconds to process each Job.

First, let’s write a simple function to pretty-display the state of the Queue over time:

let pretty state =

let count =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> 0

| Busy(_, waiting) -> 1 + waiting

let nextOut =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> "Idle"

| Busy(until, _) -> until.ToLongTimeString()

let start = state.Start.ToLongTimeString()

let nextIn = state.NextIn.ToLongTimeString()

printfn "Start: %s, Count: %i, Next in: %s, Next out: %s" start count nextIn nextOut

Now we can define our model:

let constantTime (interval: TimeSpan) =

let ticks = interval.Ticks

fun () -> interval

let arrivalTime = new TimeSpan(0,0,10);

let processTime = new TimeSpan(0,0,5)

let simpleArr = constantTime arrivalTime

let simpleProc = constantTime processTime

let startTime = new DateTime(2010, 1, 1)

let constantCase = simulate startTime simpleArr simpleProc

Let’s simulate 10 transitions in fsi:

> Seq.take 10 constantCase |> Seq.iter pretty;;

Start: 12:00:00 AM, Count: 0, Next in: 12:00:10 AM, Next out: Idle

Start: 12:00:10 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:20 AM, Next out: 12:00:15 AM

Start: 12:00:15 AM, Count: 0, Next in: 12:00:20 AM, Next out: Idle

Start: 12:00:20 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:30 AM, Next out: 12:00:25 AM

Start: 12:00:25 AM, Count: 0, Next in: 12:00:30 AM, Next out: Idle

Start: 12:00:30 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:40 AM, Next out: 12:00:35 AM

Start: 12:00:35 AM, Count: 0, Next in: 12:00:40 AM, Next out: Idle

Start: 12:00:40 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:50 AM, Next out: 12:00:45 AM

Start: 12:00:45 AM, Count: 0, Next in: 12:00:50 AM, Next out: Idle

Start: 12:00:50 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:01:00 AM, Next out: 12:00:55 AM

val it : unit = ()

Looks like we are doing something right – the simulation displays an arrival every 10 seconds, followed by 5 seconds of activity until the job is processed, and 5 seconds of Idleness until the next arrival.

Let’s do something a bit more complicated – arrivals with random, uniformly distributed inter-arrival times:

let uniformTime (seconds: int) =

let rng = new Random()

fun () ->

let t = rng.Next(seconds + 1)

new TimeSpan(0, 0, t)

let uniformArr = uniformTime 10

let uniformCase = simulate startTime uniformArr simpleProc

Here, arrival times will take any value (in seconds) between 0 and 10, included – with an average of 5 seconds between arrivals. A quick run in fsi produces the following sample:

> Seq.take 10 uniformCase |> Seq.iter pretty;;

Start: 12:00:00 AM, Count: 0, Next in: 12:00:02 AM, Next out: Idle

Start: 12:00:02 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:03 AM, Next out: 12:00:07 AM

Start: 12:00:03 AM, Count: 2, Next in: 12:00:11 AM, Next out: 12:00:07 AM

Start: 12:00:07 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:11 AM, Next out: 12:00:12 AM

Start: 12:00:11 AM, Count: 2, Next in: 12:00:11 AM, Next out: 12:00:12 AM

Start: 12:00:11 AM, Count: 3, Next in: 12:00:16 AM, Next out: 12:00:12 AM

Start: 12:00:12 AM, Count: 2, Next in: 12:00:16 AM, Next out: 12:00:17 AM

Start: 12:00:16 AM, Count: 3, Next in: 12:00:24 AM, Next out: 12:00:17 AM

Start: 12:00:17 AM, Count: 2, Next in: 12:00:24 AM, Next out: 12:00:22 AM

Start: 12:00:22 AM, Count: 1, Next in: 12:00:24 AM, Next out: 12:00:27 AM

val it : unit = ()

Not surprisingly, given the faster arrivals, we see the Queue getting slightly backed up, with Jobs waiting to be processed.

How would the Queue look like after, say, 1,000,000 transitions? Easy enough to check:

> Seq.nth 1000000 uniformCase |> pretty;;

Start: 10:36:23 PM, Count: 230, Next in: 10:36:25 PM, Next out: 10:36:28 PM

val it : unit = ()

Interesting – looks like the Queue is getting backed up quite a bit as time goes by. This is a classic result with Queues: the utilization rate, defined as arrival rate / departure rate, is saturated. When the utilization rate is strictly less than 100%, the Queue is stable, and otherwise it will build up over time, accumulating a backlog of Jobs.

Let’s create a third type of model, with Exponential rates:

let exponentialTime (seconds: float) =

let lambda = 1.0 / seconds

let rng = new Random()

fun () ->

let t = - Math.Log(rng.NextDouble()) / lambda

let ticks = t * (float)TimeSpan.TicksPerSecond

new TimeSpan((int64)ticks)

let expArr = exponentialTime 10.0

let expProc = exponentialTime 7.0

let exponentialCase = simulate startTime expArr expProc

The arrivals and processing times are exponentially distributed, with an average time expressed in seconds. In our system, we expect new Jobs to arrive on average every 10 seconds, varying between 0 and + infinity, and Jobs take 7 seconds on average to process. The queue is not saturated, and should therefore not build up, which we can verify:

> Seq.nth 1000000 exponentialCase |> pretty;;

Start: 8:55:36 PM, Count: 4, Next in: 8:55:40 PM, Next out: 8:55:36 PM

val it : unit = ()

A queue where both arrivals and processing times follow that distribution is a classic in Queuing Theory, known as a M/M/1 queue. It is of particular interest because some of its characteristics can be derived analytically – we’ll revisit that later.

Measuring performance

We already saw a simple useful measurement for Queues, the utilization rate, which defines whether our Queue will explode or stabilize over time. This is important but crude – what we would really be interested in is measuring how much of a bottleneck the Queue creates. Two measures come to mind in this frame: how long is the Queue on average, and how much time does a Job take to go through the entire system (queue + processing)?

Let’s begin with the Queue length. On average, how many Jobs should we expect to see in the Queue (including Jobs being currently processed)?

The question is less trivial than it looks. We could naively simulate a Sequence of States, and average out the number of Jobs in each State, but this would be incorrect. To understand the issue, let’s consider a Queue with constant arrivals and processing times, where Jobs arrive every 10 seconds and take 1 second to process. The result will be alternating 0s and 1s – which would give a naïve average of 0.5 Jobs in queue. However, the system will be Busy for 1 seconds, and Idle for 9 seconds, with an average number of Jobs of 0.1 over time.

To correctly compute the average, we need to compute a weighted average, counting the number of jobs present in a state, weighted by the time the System spent in that particular state.

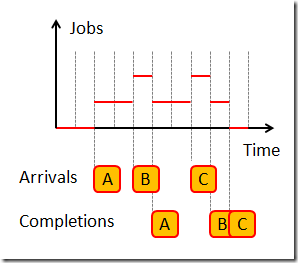

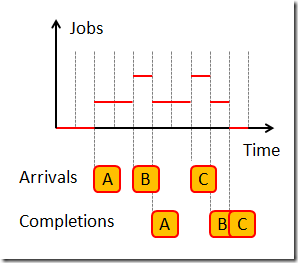

Let’s consider for illustration the example above, where we observe a Queue for 10 seconds, with 3 Jobs A, B, C arriving and departing. The average number of Jobs in the System is 3 seconds with 0, 5 seconds with 1 and 2 seconds with 2, which would give us (3x0 + 5x1 + 2x2)/10, i.e. 9/10 or 0.9 Jobs on average. We could achieve the same result by accumulating the computation over time, starting at each transition point: 2s x 0 + 2s x 1 + 1s x 2 + 2s x 1 + 1s x 2 + 1s x 1 + 1s x 0 = 9 “Jobs-seconds”, which over 10 seconds gives us the same result as before.

Let’s implement this. We will compute the average using an Accumulator, using Sequence Scan: for each State of the System, we will measure how much time was spent, in Ticks, as well as how many Jobs were in the System during that period, and accumulate the total number of ticks since the Simulation started, as well as the total number of “Jobs-Ticks”, so that the average until that point will simply be:

Average Queue length = sum of Job-Ticks / sum of Ticks.

let averageCountIn (transitions: State seq) =

// time spent in current state, in ticks

let ticks current next =

next.Start.Ticks - current.Start.Ticks

// jobs in system in state

let count state =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> (int64)0

| Busy(until, c) -> (int64)c + (int64)1

// update state = total time and total jobsxtime

// between current and next queue state

let update state pair =

let current, next = pair

let c = count current

let t = ticks current next

(fst state) + t, (snd state) + (c * t)

// accumulate updates from initial state

let initial = (int64)0, (int64)0

transitions

|> Seq.pairwise

|> Seq.scan (fun state pair -> update state pair) initial

|> Seq.map (fun state -> (float)(snd state) / (float)(fst state))

Let’s try this on our M/M/1 queue, the exponential case described above:

> averageCountIn exponentialCase |> Seq.nth 1000000 ;;

val it : float = 2.288179686

According to theory, for an M/M/1 Queue, that number should be rho / (1-rho), i.e. (7/10) / (1-(7/10)), which gives 2.333. Close enough, I say.

Let’s look at the Response Time now, that is, the average time it takes for a Job to leave the system once it entered the queue.

We’ll use an idea similar to the one we used for the average number of Jobs in the System. On our illustration, we can see that A stays in for 3 seconds, B for 4s and C for 2 seconds. In that case, the average is time A + time B + time C / 3 jobs, i.e. (3 + 4 + 2)/3 = 3 seconds. But we can also decompose the time spent by A, B and C in the system by summing up not by Job, but by period between transitions. In this case, we would get Time spent by A, B, C = 2s x 0 jobs + 2s x 1 job + 1s x 2 jobs + 2s x 1 job + 1s x 2 jobs + 1s x 1 job + 1s x 0 jobs = 9 “job-seconds”, which would give us the correct total time we need.

We can use that idea to implement the average time spent in the system in the same fashion we did the average jobs in the system, by accumulating the measure as the sequence of transition unfolds:

let averageTimeIn (transitions: State seq) =

// time spent in current state, in ticks

let ticks current next =

next.Start.Ticks - current.Start.Ticks

// jobs in system in state

let count state =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> (int64)0

| Busy(until, c) -> (int64)c + (int64)1

// count arrivals

let arrival current next =

if count next > count current then (int64)1 else (int64)0

// update state = total time and total arrivals

// between current and next queue state

let update state pair =

let current, next = pair

let c = count current

let t = ticks current next

let a = arrival current next

(fst state) + a, (snd state) + (c * t)

// accumulate updates from initial state

let initial = (int64)0, (int64)0

transitions

|> Seq.pairwise

|> Seq.scan (fun state pair -> update state pair) initial

|> Seq.map (fun state ->

let time = (float)(snd state) / (float)(fst state)

new TimeSpan((int64)time))

Trying this out on our M/M/1 queue, we theoretically expect an average of 23.333 seconds, and get 22.7 seconds:

> averageTimeIn exponentialCase |> Seq.nth 1000000 ;;

val it : TimeSpan = 00:00:22.7223798 {Days = 0;

Hours = 0;

Milliseconds = 722;

Minutes = 0;

Seconds = 22;

Ticks = 227223798L;

TotalDays = 0.0002629905069;

TotalHours = 0.006311772167;

TotalMilliseconds = 22722.3798;

TotalMinutes = 0.37870633;

TotalSeconds = 22.7223798;}

Given the somewhat sordid conversions between Int64, floats and TimeSpan, this seems plausible enough.

A practical example

Now that we got some tools at our disposition, let’s look at a semi-realistic example. Imagine a subway station, with 2 turnstiles (apparently also known as “Baffle Gates”), one letting people in, one letting people out. On average, it takes 4 seconds to get a person through the Turnstile (some people are more baffled than others) – we’ll model the processing time as an Exponential.

Now imagine that, on average, passengers arrive to the station every 5 seconds. We’ll model that process as an exponential too, even tough it’s fairly unrealistic to assume that the rate of arrival remains constant throughout the day.

// turnstiles admit 1 person / 4 seconds

let turnstileProc = exponentialTime 4.0

// passengers arrive randomly every 5s

let passengerArr = exponentialTime 5.0

Assuming the Law of conservation applies to subway station passengers too, we would expect the average rate of exit from the station to also be one every 5 seconds. However, unlike passengers coming in the station, passengers exiting arrived there by subway, and are therefore likely to arrive in batches. We’ll make the totally realistic assumption here that trains are never late, and arrive like clockwork at constant intervals, bringing in the same number of passengers. If trains arrive every 30 seconds, to maintain our average rate of 1 passenger every 5 seconds, each train will carry 6 passengers:

let batchedTime seconds batches =

let counter = ref 0

fun () ->

counter := counter.Value + 1

if counter.Value < batches

then new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0)

else

counter := 0

new TimeSpan(0, 0, seconds)

// trains arrive every 30s with 5 passengers

let trainArr = batchedTime 30 6

How would our 2 Turnstiles behave? Let’s check:

// passengers arriving in station

let queueIn = simulate startTime passengerArr turnstileProc

// passengers leaving station

let queueOut = simulate startTime trainArr turnstileProc

let prettyWait (t:TimeSpan) = t.TotalSeconds

printfn "Turnstile to get in the Station"

averageCountIn queueIn |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> printfn "In line: %f"

averageTimeIn queueIn |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> prettyWait |> printfn "Wait in secs: %f"

printfn "Turnstile to get out of the Station"

averageCountIn queueOut |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> printfn "In line: %f"

averageTimeIn queueOut |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> prettyWait |> printfn "Wait in secs: %f";;

Turnstile to get in the Station

In line: 1.917345

Wait in secs: 9.623852

Turnstile to get out of the Station

In line: 3.702664

Wait in secs: 18.390027

The results fits my personal experience: the Queue at the exit gets backed up quite a bit, and passengers have to wait an average 18.4 seconds to exit the Station, while it takes them only 9.6 seconds to get in.

It also may seem paradoxical. People are entering and exiting the Station at the same rate, and turnstiles process passengers at the same speed, so how can we have such different behaviors at the two turnstiles?

The first point here is that Queuing processes can be counter-intuitive, and require thinking carefully about what is being measured, as we saw earlier with the performance metrics computations.

The only thing which differs between the 2 turnstiles is the way arrivals are distributed over time – and that makes a lot of difference. Arrivals are fairly evenly spaced, and there is a good chance that a Passenger who arrives to the Station finds no one in the Queue, and in that case, he will wait only 4 seconds on average. By contrast, when passengers exit, they arrive in bunches, and only the first one will find no-one in the Queue – all the others will have to wait for that first person to pass through before getting their chance, and therefore have by default a much larger “guaranteed wait time”.

That’s it for today! There is much more to Queuing than single-queues (if you are into probability and Markov chains, networks of Queues are another fascinating area), but we will leave that for another time. I hope you’ll have found this excursion in Queuing interesting and maybe even useful. I also thought this was an interesting topic illustrating F# Sequences – and I am always looking forward to feedback!

Complete code (F# script) is also available on FsSnip.net

open System

// Queue / Server is either Idle,

// or Busy until a certain time,

// with items queued for processing

type Status = Idle | Busy of DateTime * int

type State =

{ Start: DateTime;

Status: Status;

NextIn: DateTime }

let next arrival processing state =

match state.Status with

| Idle ->

{ Start = state.NextIn;

NextIn = state.NextIn + arrival();

Status = Busy(state.NextIn + processing(), 0) }

| Busy(until, waiting) ->

match (state.NextIn <= until) with

| true ->

{ Start = state.NextIn;

NextIn = state.NextIn + arrival();

Status = Busy(until, waiting + 1) }

| false ->

match (waiting > 0) with

| true ->

{ Start = until;

Status = Busy(until + processing(), waiting - 1);

NextIn = state.NextIn }

| false ->

{ Start = until;

Status = Idle;

NextIn = state.NextIn }

let simulate startTime arr proc =

let nextIn = startTime + arr()

let state =

{ Start = startTime;

Status = Idle;

NextIn = nextIn }

Seq.unfold (fun st ->

Some(st, next arr proc st)) state

let pretty state =

let count =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> 0

| Busy(_, waiting) -> 1 + waiting

let nextOut =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> "Idle"

| Busy(until, _) -> until.ToLongTimeString()

let start = state.Start.ToLongTimeString()

let nextIn = state.NextIn.ToLongTimeString()

printfn "Start: %s, Count: %i, Next in: %s, Next out: %s" start count nextIn nextOut

let constantTime (interval: TimeSpan) =

let ticks = interval.Ticks

fun () -> interval

let arrivalTime = new TimeSpan(0,0,10);

let processTime = new TimeSpan(0,0,5)

let simpleArr = constantTime arrivalTime

let simpleProc = constantTime processTime

let startTime = new DateTime(2010, 1, 1)

let constantCase = simulate startTime simpleArr simpleProc

printfn "Constant arrivals, Constant processing"

Seq.take 10 constantCase |> Seq.iter pretty;;

let uniformTime (seconds: int) =

let rng = new Random()

fun () ->

let t = rng.Next(seconds + 1)

new TimeSpan(0, 0, t)

let uniformArr = uniformTime 10

let uniformCase = simulate startTime uniformArr simpleProc

printfn "Uniform arrivals, Constant processing"

Seq.take 10 uniformCase |> Seq.iter pretty;;

let exponentialTime (seconds: float) =

let lambda = 1.0 / seconds

let rng = new Random()

fun () ->

let t = - Math.Log(rng.NextDouble()) / lambda

let ticks = t * (float)TimeSpan.TicksPerSecond

new TimeSpan((int64)ticks)

let expArr = exponentialTime 10.0

let expProc = exponentialTime 7.0

let exponentialCase = simulate startTime expArr expProc

printfn "Exponential arrivals, Exponential processing"

Seq.take 10 exponentialCase |> Seq.iter pretty;;

let averageCountIn (transitions: State seq) =

// time spent in current state, in ticks

let ticks current next =

next.Start.Ticks - current.Start.Ticks

// jobs in system in state

let count state =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> (int64)0

| Busy(until, c) -> (int64)c + (int64)1

// update state = total time and total jobsxtime

// between current and next queue state

let update state pair =

let current, next = pair

let c = count current

let t = ticks current next

(fst state) + t, (snd state) + (c * t)

// accumulate updates from initial state

let initial = (int64)0, (int64)0

transitions

|> Seq.pairwise

|> Seq.scan (fun state pair -> update state pair) initial

|> Seq.map (fun state -> (float)(snd state) / (float)(fst state))

let averageTimeIn (transitions: State seq) =

// time spent in current state, in ticks

let ticks current next =

next.Start.Ticks - current.Start.Ticks

// jobs in system in state

let count state =

match state.Status with

| Idle -> (int64)0

| Busy(until, c) -> (int64)c + (int64)1

// count arrivals

let arrival current next =

if count next > count current then (int64)1 else (int64)0

// update state = total time and total arrivals

// between current and next queue state

let update state pair =

let current, next = pair

let c = count current

let t = ticks current next

let a = arrival current next

(fst state) + a, (snd state) + (c * t)

// accumulate updates from initial state

let initial = (int64)0, (int64)0

transitions

|> Seq.pairwise

|> Seq.scan (fun state pair -> update state pair) initial

|> Seq.map (fun state ->

let time = (float)(snd state) / (float)(fst state)

new TimeSpan((int64)time))

// turnstiles admit 1 person / 4 seconds

let turnstileProc = exponentialTime 4.0

// passengers arrive randomly every 5s

let passengerArr = exponentialTime 5.0

let batchedTime seconds batches =

let counter = ref 0

fun () ->

counter := counter.Value + 1

if counter.Value < batches

then new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0)

else

counter := 0

new TimeSpan(0, 0, seconds)

// trains arrive every 30s with 5 passengers

let trainArr = batchedTime 30 6

// passengers arriving in station

let queueIn = simulate startTime passengerArr turnstileProc

// passengers leaving station

let queueOut = simulate startTime trainArr turnstileProc

let prettyWait (t:TimeSpan) = t.TotalSeconds

printfn "Turnstile to get in the Station"

averageCountIn queueIn |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> printfn "In line: %f"

averageTimeIn queueIn |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> prettyWait |> printfn "Wait in secs: %f"

printfn "Turnstile to get out of the Station"

averageCountIn queueOut |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> printfn "In line: %f"

averageTimeIn queueOut |> Seq.nth 1000000 |> prettyWait |> printfn "Wait in secs: %f"