Decision Tree classification

05 Aug 2012Machine Learning in Action, in F#

Porting Machine Learning in Action from Python to F#

- KNN classification (1)

- KNN classification (2)

- Decision Tree classification

- Naive Bayes classification

- Logistic Regression classification

- SVM classification (1)

- SVM classification (2)

- AdaBoost classification

- K-Means clustering

- SVD

- Recommendation engine

- Code on GitHub

Today’s topic will be Chapter 3 of “Machine Learning in Action”, which covers Decision Trees.

Disclaimer: I am new to Machine Learning, and claim no expertise on the topic. I am currently reading Machine Learning in Action, and thought it would be a good learning exercise to convert the book’s samples from Python to F#.

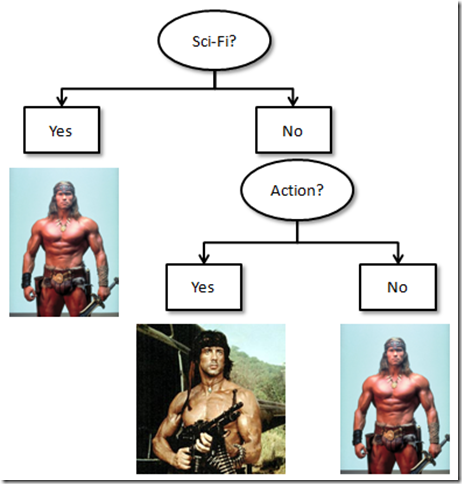

The idea behind Decision Trees is similar to the Game of 20 Questions: construct a set of discrete Choices to identify the Class of an item. We will use the following dataset for illustration: imagine that we have 5 cards, each with a major masterpiece of contemporary cinema, classified by genre. Now I hide one - and you can ask 2 questions about the genre of the movie to identify the Thespian luminary in the lead role, in as few questions as possible:

| Action | Sci-Fi | Actor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cliffhanger | Yes | No | Stallone |

| Rocky | Yes | No | Stallone |

| Twins | No | No | Schwarzenegger |

| Terminator | Yes | Yes | Schwarzenegger |

| Total Recall | Yes | Yes | Schwarzenegger |

The questions you would likely ask are:

- Is this a Sci-Fi movie? If yes, Arnold is the answer, if no,

- Is this an Action movie? if yes, go for Sylvester, otherwise Arnold it is.

That’s a Decision Tree in a nutshell: we traverse a Tree, asking about features, and depending on the answer, we draw a conclusion or recurse deeper into more questions. The goal today is to let the computer build the right tree from the dataset, and use that tree to classify “subjects”.

Defining a Tree

Let’s start with the end - the Tree. A common and convenient way to model Trees in F# is to use a discriminated union like this:

type Tree =

| Conclusion of string

| Choice of string * (string * Tree) []

A Tree is composed of either a Conclusion, described by a string, or a Choice, which is described by a string, and an Array of multiple options, each described by a string and its own Tree, “tupled”.

For instance, we can manually create a tree for our example like this:

let manualTree =

Choice

("Sci-Fi",

[|("No",

Choice

("Action",

[|("Yes", Conclusion "Stallone");

("No", Conclusion "Schwarzenegger")|]));

("Yes", Conclusion "Schwarzenegger")|])

Our tree starts with a Choice, labeled “Sci-Fi”, with 2 options in an Array, “No” or “Yes”. “Yes” leads to a Conclusion (a Leaf node), Arnold, while “No” opens another Choice, “Action”, with 2 Conclusions.

So how can we use this to Classify a “Subject”? We need to traverse down the Tree, check what branch corresponds to the Subject for the current Choice, and continue until we reach a Decision node, at what point we can return the contents of the Conclusion. To that effect, we’ll represent a “Subject” (the thing we are trying to classify) as an collection of Tuples, each Tuple being a key/value pair, representing a Feature and its value:

let test = [| ("Action", "Yes"); ("Sci-Fi", "Yes") |]

We are ready to write a classification function now:

let rec classify subject tree =

match tree with

| Conclusion(c) -> c

| Choice(label, options) ->

let subjectState =

subject

|> Seq.find(fun (key, value) -> key = label)

|> snd

options

|> Array.find (fun (option, tree) -> option = subjectState)

|> snd

|> classify subject

classify is a recursive function: given a subject and a tree, if the Tree is a Conclusion, we are done, otherwise, we retrieve the label of the next Choice, find the value of the Subject for that Choice, and use it to pick the next level of the Tree.

At that point, using the Tree to classify our subject is as simple as:

> let actor = classify test manualTree;;

val actor : string = "Schwarzenegger"

Not bad for 14 lines of code. The most painful part is the manual construction of the Tree - let’s see if we can get the computer to build that for us.

So what…s a good question?

So how could we go about constructing a “good” tree based on the data, that is, a good sequence of questions?

The first consideration here is how informative the answer to a question is. An answer is very informative if it helps us separate the dataset into very differentiated groups, groups which are different from each other and internally homogeneous. A question which helps us break the dataset into 2 groups, the first containing only “Schwarzenegger” movies, the other only “Stallone” movies, would be perfect. A question which splits the dataset into groups with a half/half mix of movies by each actor would be totally useless.

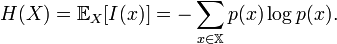

To quantify the “internally homogeneous” notion, we will use Shannon Entropy, which is defined as

Shannon Entropy formula, courtesy of Wikipedia

I won’t go into a full discussion on Entropy today (if you want to know more, you may find this older post of interest) - the short version is, it provides a measure for how “disorganized” a set is. The lower the Entropy, the more predictable the content: a set where all results are identical would have a 0 entropy, while a set where all results are equally probably will result in an entropy value that is maximal.

The second consideration is, how much information do we gain by asking one question versus the other. If we look back at our dataset, there are 2 questions we could ask first: Sci-Fi or Action. If we asked “is it an Action movie” as an opener, there is a 20% chance that we are done and can conclude “Schwarzenegger”, but in 80% of the cases, we are left with a 50/50 chance of guessing the right actor. By contrast, if we ask “is it a Sci-Fi movie” first, there is a 40% chance that we are done, with a perfect Entropy group of Schwarzenegger movies, and only a 60% chance of a not-so-useful answer.

We can quantify this - how informative is each question - by considering the expected gain in Entropy: for a question, consider the conclusion of each possible answer and compute its Entropy, and average out the Entropy of receiving each answer, weighted by the probability of obtaining that answer.

Let’s illustrate on our dataset. Asking “Action?” can produce 2 outcomes:

- Yes, with 20% probability: we have now a 100% chance of Schwarzenegger, with a 0 Entropy

- No, with 80% probability: we have now a 50/50 chance of either actor, with a 0.69 Entropy

By contrast, asking “Sci-Fi?” first can produce 2 outcomes:

- Yes, with 40% probability: we have now a 100% chance of Schwarzenegger, with a 0 Entropy

- No, with 60% probability: we have now a 33.3%/66.7% chance of either actor, with a 0.64 Entropy

Case 1 gives us 0.8 x 0.69 value, case 2 0.6 x 0.64 - a much lower Entropy for a much better question.

The final consideration is whether the question is informative at all, which we can translate as “is our Entropy better after we ask the question”? For instance, if we know it’s a Sci-Fi movie, asking whether it’s an Action movie brings us nothing at all: the expected Entropy after the question isn’t better than our initial Entropy. If a Question doesn’t result in a higher expected Entropy, we shouldn’t even bother to ask the Question.

Another way to consider what we just discussed is from a Decision Theory standpoint. In that context, information is considered valuable if having the information available would result in making a different decision. If for any answer to the question, the decision remains identical to what it would have been without it, the information is worthless - and if offered the choice between multiple pieces of information, one should pick the most likely to produce a better decision.

Automatic Creation of the Tree using Entropy

Let’s put these concepts into action, and figure out how to construct a good decision tree from the dataset. The outline of the algorithm is the following:

- Given a dataset, consider each Feature/Question available, split the dataset according to that Feature, and compute the Entropy that would be gained by splitting on that Feature,

- Pick the Feature that results in the highest Entropy gain, and split the dataset accordingly into subsets corresponding to each possible “answer”,

- For each of the subsets, repeat the procedure, until no information is gained,

- When no Entropy is gained by asking further questions, return the most frequent Conclusion in the subset.

On our example, this would result in the following sequence:

- Sci-Fi has a better Entropy gain than Action: break into 2 subsets, Sci-Fi and non-Sci-Fi movies,

- For the Sci-Fi group, do we gain Entropy by asking about Action? No , stop,

- For the non-Sci-Fi group, asking about Action still produces information; after that, stop - there is no question left.

Rather than build up step-by-step, I’ll dump the whole tree-building code here and comment afterwards:

let prop count total = (float)count / (float)total

let inspect dataset =

let header, (data: 'a [][]) = dataset

let rows = data |> Array.length

let columns = header |> Array.length

header, data, rows, columns

let h vector =

let size = vector |> Array.length

vector

|> Seq.groupBy (fun e -> e)

|> Seq.sumBy (fun e ->

let count = e |> snd |> Seq.length

let p = prop count size

- p * log p)

let entropy dataset =

let _, data, _, cols = inspect dataset

data

|> Seq.map (fun row -> row.[ cols-1 ])

|> Seq.toArray

|> h

let remove i vector =

let size = vector |> Array.length

Array.append vector.[ 0 .. i-1 ] vector.[ i+1 .. size-1 ]

let split dataset i =

let hdr, data, _, _ = inspect dataset

remove i hdr,

data

|> Seq.groupBy (fun row -> row.[i])

|> Seq.map (fun (label, group) ->

label,

group |> Seq.toArray |> Array.map (remove i))

let splitEntropy dataset i =

let _, data, rows, cols = inspect dataset

data

|> Seq.groupBy(fun row -> row.[i])

|> Seq.map (fun (label, group) ->

group

|> Seq.map (fun row -> row.[cols - 1])

|> Seq.toArray)

|> Seq.sumBy (fun subset ->

let p = prop (Array.length subset) rows

p * h subset)

let selectSplit dataset =

let hdr, data, _, cols = inspect dataset

if cols < 2

then None

else

let currentEntropy = entropy dataset

let feature =

hdr.[0 .. cols - 2]

|> Array.mapi (fun i f ->

(i, f), currentEntropy - splitEntropy dataset i)

|> Array.maxBy (fun f -> snd f)

if (snd feature > 0.0) then Some(fst feature) else None

let majority dataset =

let _, data, _, cols = inspect dataset

data

|> Seq.groupBy (fun row -> row.[cols-1])

|> Seq.maxBy (fun (label, group) -> Seq.length group)

|> fst

let rec build dataset =

match selectSplit dataset with

| None -> Conclusion(majority dataset)

| Some(feature) ->

let (index, name) = feature

let (header, groups) = split dataset index

let trees =

groups

|> Seq.map (fun (label, data) -> (label, build (header, data)))

|> Seq.toArray

Choice(name, trees)

prop is a simple utility function which converts the count of items from a total in a float proportion.

inspect is a utility function which extracts useful information from a dataset. I noticed I was doing variations of the same operations everywhere, so I ended up extracting it in a function. The dataset is modeled as a Tuple, where the first element is an array of headers, representing the names of each Feature, and the second is an Array of Arrays, representing a list of observations. The feature we are classifying on is expected to be in the last column of the dataset.

h computes the Shannon Entropy of a vector (an Array of values). entropy extracts the vector we are classifying on, and computes its Shannon Entropy.

remove is a simple utility function, which removes the ith component of a vector. It is used in split, a function which takes a dataset and splits it according to feature i. split returns a Tuple, where the first element is the updated header (with the split-feature removed), and a Sequence containing each value of the feature, with the corresponding reduced dataset. For instance, splitting the movies dataset on feature 1 (“Sci-Fi”) produces the following:

> split movies 1;;

val it : string [] * seq<string * string [] []> =

([|"Action"; "Actor"|],

seq

[("No",

[|[|"Yes"; "Stallone"|]; [|"Yes"; "Stallone"|];

[|"No"; "Schwarzenegger"|]|]);

("Yes", [|[|"Yes"; "Schwarzenegger"|]; [|"Yes"; "Schwarzenegger"|]|])])

Sci-Fi is now gone from the Headers, and 2 groups have been produced, corresponding to Non-Sci-Fi and Sci-Fi movies, with the corresponding reduced dataset.

splitEntropy computes the expected Entropy that would result from splitting on feature i. It splits the dataset on the value in column i (the feature we would split on), retrieves the value of the last column (the feature we are classifying on) and computes the sum of the entropies, weighted proportionally to the size of each sub-group (the probability to get that answer). selectSplit builds on it, and computes the entropy gain achieved by splitting on each of the available features (if there is any feature left), and picks the feature with maximum gain, if it is higher than the current situation.

majority is a simple utility function, which returns the most-frequent value in a dataset.

Finally, build puts all of this together and recursively builds the Decision Tree. If there is no feature to split on (no information gain left), it produces a Conclusion, containing the majority of elements in the current dataset. Otherwise, the dataset is split on the best feature, and a Choice node is created, which is populated with a Tree corresponding to the action taken for each possible outcome of the Feature we are splitting on.

That was a lot of code to go through (actually, under 100 lines, not too bad) - let’s get our reward, and try it out:

> let movies =

[| "Action"; "Sci-Fi"; "Actor" |],

[| [| "Yes"; "No"; "Stallone" |];

[| "Yes"; "No"; "Stallone" |];

[| "No"; "No"; "Schwarzenegger" |];

[| "Yes"; "Yes"; "Schwarzenegger" |];

[| "Yes"; "Yes"; "Schwarzenegger" |] |]

let tree = build movies

let subject = [| ("Action", "Yes"); ("Sci-Fi", "No") |]

let answer = classify subject tree;;

val movies : string [] * string [] [] =

([|"Action"; "Sci-Fi"; "Actor"|],

[|[|"Yes"; "No"; "Stallone"|]; [|"Yes"; "No"; "Stallone"|];

[|"No"; "No"; "Schwarzenegger"|]; [|"Yes"; "Yes"; "Schwarzenegger"|];

[|"Yes"; "Yes"; "Schwarzenegger"|]|])

val tree : Tree =

Choice

("Sci-Fi",

[|("No",

Choice

("Action",

[|("Yes", Conclusion "Stallone");

("No", Conclusion "Schwarzenegger")|]));

("Yes", Conclusion "Schwarzenegger")|])

val subject : (string * string) [] = [|("Action", "Yes"); ("Sci-Fi", "No")|]

val answer : string = "Stallone"

Looks like we are doing something right!

Real data

The book demonstrates the algorithm on the lenses dataset, which focuses on what contact lenses to prescribe to patients in various conditions, and can be found at the wonderful collection of test datasets maintained at the UC Irvine Machine Learning Repository. I tried it out, and got the same tree as the author. I also tested it on the Nursery dataset (I am still not 100% clear on the details of that dataset, but I have to admit I cracked up when I read the description for attribute 1: “parents: usual, pretentious, great_pret”…), which is significantly larger (12,960 records); the algorithm went through it like a champ, and produced an ungodly tree which I am not even going to try to reproduce here.

I haven’t found a good way to plot the resulting Decision Trees yet, so I’ll leave it at that - running the algorithm on these datasets is pretty straightforward.

Conclusion

The code conversion for this chapter was interesting. The part where F# really shines is the Tree representation as a Discriminated Union, which combined with pattern-matching works wonders in manipulating Trees, and seems to me cleaner than the equivalent Python code using nested dictionaries.

I spent quite a bit of time second-guessing myself on how to organize the dataset itself - one array, labels + data, headers, data and “feature of interest”, 2-d array or array of arrays… There is a lot of unpleasant grouping and array manipulations going on in the splitting / feature selection part, and I have a nagging feeling that there has to be a representation that allows for clearer transformations - and clearer return types. However, the code remains reasonably readable, and Seq.groupBy does in one line all the unique keys identification and counting that is more involved in the Python code.

The piece I have completely left out from Chapter 3 is persisting and plotting Decision Trees. I may go back to the plotting part at some later time, but my first impression is that this will be no piece of cake, and I…d rather focus on the algorithms at that point in time. If you know of a good and free F# tree-plotting library, let me know!

Finally, I decided to put this code on GitHub. It…s my first repository there, so please be patient and let me know if there are things I can do to make that repository better!

Machine Learning in Action, in F#, on GitHub

Questions, comments? Let me know your feedback!