Kaggle/StackOverflow contest field notes, part 1

10 Nov 2012The Kaggle/StackOverflow contest officially closed a few days ago, which makes it a perfect time to have a miniature retrospective on that experience. The objective of the contest was to write an algorithm to predict whether a StackOverflow question would be closed by moderators, and the reason why.

The contest was announced just a couple of days before what was supposed to be 4 weeks of computer-free vacation travelling around Europe. Needless to say, a quick change of plans followed; I am a big fan of StackOverflow, and Machine Learning has been on my mind quite a bit lately, so I packed my smallest laptop with Visual Studio installed. At the same time, the wonders of the Interwebs resulted in the formation of Team Charon - the awesome @lu_a_jalla and me, around the loosely defined project of “having fun with this, using 100% F#”.

@brandewinder you got me there, are you a team player? ;)

— Natallie Baikevich (@lu_a_jalla) August 21, 2012

Now that the contest is over, here are a few notes on the experience, focusing on process and tools, and not the modeling aspects – I’ll get back to that in a later post.

This is my first unquestionably positive experience with a dispersed team - every morning I was genuinely looking forward to code check-ins, something I can’t say of every experience I have had with remote teams. I recall reading somewhere that there was only one valid reason to work with a dispersed team: when you really want to work with that person, and it is the only way to work together. I tend to agree, and this was tremendously fun. There are not that many opportunities to have meaningful interactions involving both F# and Machine Learning, and I learnt quite a bit in the process, in large part because this was team work.

As a side note, I find it amazing how ridiculously easy it is today to set up a collaborative environment. Set up a GitHub repository, use Skype and Twitter – and you are good to go. The only thing technology hasn’t quite solved yet are these pesky time zones: Minsk and San Francisco are still 11 hours apart. This is were a team of night owls might help…

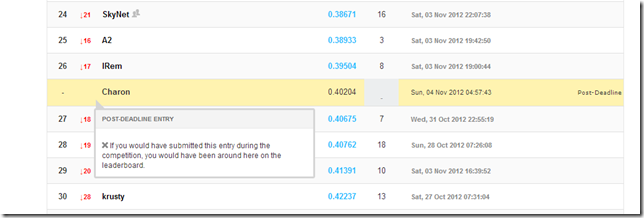

Whenever there is a deadline, make sure the when and what is clear. Had I followed this simple rule, I would have been on time for the final submission. Instead, I missed it by a couple of hours, because I didn’t check what “you have three days left” meant exactly, which is too bad, because otherwise we could have ended up in 27th position, among 160+ competitors:

… which is a result I am pretty proud of, given that this was my first “official” attempt at Machine Learning stuff, and some of the competitors looked pretty qualified. During the initial phase, we went as high as 10th position, and ended up in 40th position, in the top 25%.

F#, and specifically FSI, worked really well. From what I understand, Python and R are tools commonly used for this type of job; having no experience with either, I can’t compare, but I will say that there is no way I would have been even remotely as productive using C#. The interactive window / REPL was a life-saver: I would open the dataset file only once, start writing code “live” against the dataset, tweak it until it worked, and then save it. C# would have required re-building and re-loading data for every code change, and that would have slowed me dramatically.

I am pretty sure Python and R have more ML libraries available out-of-the-box than F#; that wasn’t really an issue here, because I really wanted to take this project as a learning opportunity, and the model we ended up with was coded entirely from scratch, in F#. We’ll talk more about that in the part about the model itself.

On a related note, script files are a double-edged sword. I used them quite a bit, because they are the natural complement to FSI, and worked well to develop exploratory models without “over-committing” to a stable model just yet. On the other hand, because scripts are not part of the solution build, they require a bit of maintenance discipline: without proper care, it’s easy to end up with a bunch of broken scripts that are sadly out-of-sync with the model.

Running analysis in Machine Learning is the new “My code’s compiling:

You folks having fun while stuff compiles don't even know about how long it takes to train/test in machine learning. Office Party!

— Richard Minerich (@rickasaurus) October 26, 2012

Having to wait for minutes, if not hours, until you can see whether a particular idea is panning out or a complete failure, is nerve-racking, and requires some adjustments to your classic developer rhythm, to avoid spending most of your time staring at the screen, waiting for a computation to come back. What was lost in “spontaneity” might have been a good thing, because it required thinking twice before launching any computation, and considering whether this was a worthwhile time investment.

This was particularly painful, since for the sake of traveling light, I took the smallest laptop that I could work with. In retrospect, I should probably have spent the time to make sure I could remote in my personal workstation. That experience also made me very interested in hearing more about {m}brace.net, which seems to address the issues I was having.

The lack of visual analysis feedback was a bit of an impediment. The first reason is my lack of familiarity with textual data. We used Naïve Bayes algorithms, and compared to domains I am familiar with, like time-series analysis, getting a sense for “what is going on with the model” wasn’t obvious. Numerical approaches like Logistic Regression, where producing charts is easier, were a bit hindered by the lack of a F# flexible and easy-to-use charting solution, geared towards data exploration. I used FSharpChart a bit, which is OK, but not super smooth.

In retrospect, the way we dealt with datasets was OK, but we might have done better. We ended up working mostly with csv files, both for inputs and models, dumped in a shared SkyDrive folder. As a result, we didn’t really have any versioning going on, and both had to tinker with the code to point to local paths on our respective machines, which was sub-optimal. I suppose taking the time to set up some proper shared storage would have simplified things, and might also have allowed us to save intermediary extractions (like word counts) in a manner easier to access and query later.

That’s all I can think of for the moment – I’ll make the GitHub repository public once I get a chance to clean it up a bit, and will then discuss the model itself.

All in all, it was a fantastic experience, and while my vacation didn’t look exactly like I had anticipated, it was extremely fun. I especially want to tip my hat to @lu_a_jalla, who was a fantastic teammate, and from whom I learnt a lot in the process. You rocked - thank you!