FsCheck + XUnit = The Bomb

22 Mar 2014A couple of days ago, I got into the following Twitter exchange:

@brandewinder do you have any link to get in touch with this combo? #fsharp

— Max Malook (@max_malook) March 21, 2014

So why do I think FsCheck + XUnit = The Bomb?

I have a long history with Test-Driven Development; to this day, I consider Kent Beck’s “Test-Driven Development by Example” one of the biggest influences in the way I write code (any terrible code I might have written is, of course, to be blamed entirely on me, and not on the book).

In classic TDD style, you typically proceed by writing incremental test cases which match your requirements, and progressively write the code that will satisfy the requirements. Let’s illustrate on an example, a password strength validator. Suppose that my requirements are “a password must be at least 8 characters long to be valid”. Using XUnit, I would probably write something along these lines:

namespace FSharpTests

open Xunit

open CSharpCode

module ``Password validator tests`` =

[<Fact>]

let ``length above 8 should be valid`` () =

let password = "12345678"

let validator = Validator ()

Assert.True(validator.IsValid(password))

… and in the CSharpCode project, I would then write the dumbest minimal implementation that could passes that requirement, that is:

public class Validator

{

public bool IsValid(string password)

{

return true;

}

}

Next, I would write a second test, to verify the obvious negative:

namespace FSharpTests

open Xunit

open CSharpCode

module ``Password validator tests`` =

[<Fact>]

let ``length above 8 should be valid`` () =

let password = "12345678"

let validator = Validator ()

Assert.True(validator.IsValid(password))

[<Fact>]

let ``length under 8 should not be valid`` () =

let password = "1234567"

let validator = Validator ()

Assert.False(validator.IsValid(password))

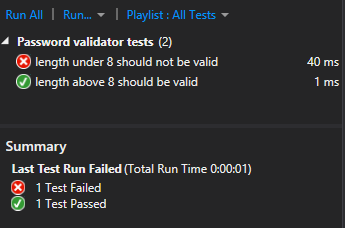

This fails, producing the following output in Visual Studio:

… which forces me to fix my implementation, for instance like this:

public class Validator

{

public bool IsValid(string password)

{

if (password.Length < 8)

{

return false;

}

return true;

}

}

Let’s pause here for a couple of remarks. First, note that while my tests are written in F#, the code base I am testing against is in C#. Mixing the two languages in one solution is a non-issue. Then, after years of writing C# test cases with names like Length_Above_8 _Should_Be_Valid, and arguing whether this was better or worse than LengthAbove8ShouldBeValid, I find that having the ability to simply write “length above 8 should be valid”, in plain old English (and seeing my tests show that way in the test runner as well), is pleasantly refreshing. For that reason alone, I would encourage F#-curious C# developers to try out writing tests in F#; it’s a nice way to get your toes in the water, and has neat advantages.

But that’s not the main point I am interested here. While this process works, it is not without issues. From a single requirement, “a password must be at least 8 characters long to be valid”, we ended up writing 2 test cases. First, the cases we ended up are somewhat arbitrary, and don’t fully reflect what they say. I only tested two instances, one 7 characters long, one 8 characters long. This is really relying on my ability as a developer to identify “interesting cases” in a vast universe of possible passwords, hoping that I happened to cover sufficient ground.

This is where FsCheck comes in. FsCheck is a port of Haskell’s QuickCheck, a property-based testing framework. The term “property” is somewhat overloaded, so let’s clarify: what “Property” means in that context is a property of our program that should be true, in the same sense as mathematically, a property of any number x is “x * x is positive”. It should always be true, for any input x.

Install FsCheck via Nuget, as well as the FsCheck XUnit extension; you can now write tests that verify properties by marking them with the attribute [<Property>], instead of [<Fact>], and the XUnit test runner will pick them up as normal tests. For instance, taking our example from right above, we can write:

namespace FSharpTests

open Xunit

open FsCheck

open FsCheck.Xunit

open CSharpCode

module Specification =

[<Property>]

let ``square should be positive`` (x:float) =

x * x > 0.

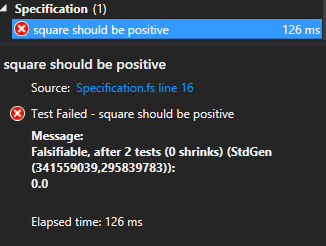

Let’s run that – fail. If you click on the test results, here is what you’ll see:

FsCheck found a counter-example, 0.0. Ooops! Our specification is incorrect here, the square value doesn’t have to be strictly positive, and could be zero. This is an obvious mistake, let’s fix the test, and get on with our lives:

[<Property>]

let ``square should be positive`` (x:float) =

x * x >= 0.

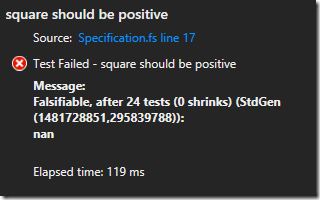

Damn – this still doesn’t pass:

FsCheck still found a counter-example, after 24 attempts: the property doesn’t hold for nan, aka “Not a Number”, which is a valid float. This is more interesting. The previous case was an obvious mistake, but I don’t know if I would have spontaneously thought about writing a test for this. First, let’s fix the test. What we want to say now is “if x is a number, then the property holds”, or, in more mathematical terms, “x is a number implies x * x is positive”, which is traditionally represented by a double arrow.

[<Property>]

let ``square should be positive`` (x:float) =

not (Double.IsNaN(x)) ==> (x * x >= 0.)

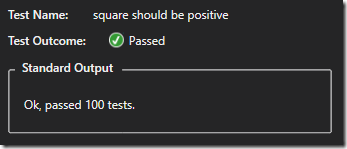

Victory – the test now passes:

In many respects, this reminds me of Pex, a tool I really enjoyed back in the days. To catch bugs, you have to think like a bug, which is difficult to do. Developers tend to focus on the happy path when writing code, and thinking about the myriads of ways things could go wrong is genuinely hard. Having a machine think about inputs, in a very mechanical way, helps overcome that.

Let’s go back to our password validation example. First, we can re-express our original tests in a way which hopefully conveys our requirements better:

[<Property>]

let ``length above 8 should be valid`` (password:string) =

let validator = Validator ()

password.Length >= 8 ==> validator.IsValid(password)

[<Property>]

let ``length under 8 should not be valid`` (password:string) =

let validator = Validator ()

password.Length < 8 ==> not (validator.IsValid(password))

No more arbitrary special cases – the test reads like the requirements.

More importantly, this comes in handy when the requirements become a bit more hairy. As an example, I would expect the password validator to do a bit more than checking for the length. For instance, I would probably want to check for a batteries of conditions, along these lines:

public interface IRule

{

bool IsSatisfied(string password);

}

public class UpperCharsRule : IRule

{

public bool IsSatisfied(string password)

{

return password.Count(Char.IsUpper) >= 1;

}

}

public class NumbersRule : IRule

{

public bool IsSatisfied(string password)

{

return password.Count(Char.IsNumber) >= 1;

}

}

public class LengthRule : IRule

{

public bool IsSatisfied(string password)

{

return password.Length >= 8;

}

}

public class PowerValidator

{

private readonly IEnumerable<irule> rules;

public PowerValidator(IEnumerable<irule> rules)

{

this.rules = rules;

}

public bool IsValid(string password)

{

return this.rules.All(rule => rule.IsSatisfied(password));

}

}

The validator now has a collection of rules, checking whether it contains at least one upper case character, at least one digit, and is at least 8 characters long. Writing individual test cases for all the possible combinations is going to become a bit unpleasant. I would typically write unit tests against each individual rules, but that still leaves me with a nasty integration test to make sure that the PowerValidator, when loaded with my 3 rules, does The Right Thing. Also, that leaves me with an unpleasant task when the requirements change, and become “3 digits at least” and “2 upper case characters at least” – all my nice edge cases I carefully crafted are now probably invalid, and need to be redone.

FsCheck makes that problem much less terrible. Instead of a myriad of test cases, I can really reduce my requirement to 2 cases: either all the rules are satisfied, in what case the password should be valid, or any of them is not satisfied, in what case the password should not be valid. Let’s do it:

[<Property>]

let ``when all rules pass, password should be valid`` (password:string) =

let rule1 = UpperCharsRule ()

let rule2 = NumbersRule ()

let rule3 = LengthRule ()

let validator = PowerValidator([rule1;rule2;rule3])

(rule1.IsSatisfied(password)

&& rule2.IsSatisfied(password)

&& rule3.IsSatisfied(password))

==> validator.IsValid(password)

[<Property>]

let ``when any rule fails, password should be invalid`` (password:string) =

let rule1 = UpperCharsRule ()

let rule2 = NumbersRule ()

let rule3 = LengthRule ()

let validator = PowerValidator([rule1;rule2;rule3])

not (rule1.IsSatisfied(password)

&& rule2.IsSatisfied(password)

&& rule3.IsSatisfied(password))

==> not (validator.IsValid(password))

Here we go – integration test complete, and passing. If you are skeptical – as you should when writing tests – let’s remove rule3 from the validator in our second test:

let validator = PowerValidator([rule1;rule2])

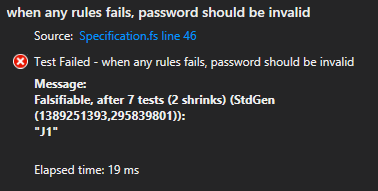

Now run the test, and you should see something like this:

Our test fails miserably, on the test case “J1”, which passes rules 1 and 2 (it contains both one character and one number), but not rule 3. FsCheck IS doing the right thing.

I will leave it at that for today. There is more to FsCheck than what I presented here, but I hope you are now convinced that FsCheck and XUnit is indeed The Bomb, or at the very least a combination you should be looking into, if you haven’t yet. FsCheck brings power and expressiveness to your tests, and XUnit ease-of-use and smooth integration.

If you found the topic interesting, I also highly recommend Scott Wlaschin’s recent post, where he goes through the Roman Numerals Kata, and demonstrates how one could go about solving it in a slightly different Test-Driven way, using FsCheck and higher level requirements instead – and what type of design you might end up with going that route.