Some completely useless fun with the logistic map

26 Oct 2014From time to time, I get absorbed by questions for no clear reason. This is one of these times – you have been warned.

So here is the question: can I use a logistic map to encode an arbitrary list of 1s and 0s into a single float, and generate back the series by applying the logistic map? I don’t think there is a clear theoretical or practical interest in this question, but for some reason I couldn’t shake it off, and had to do it.

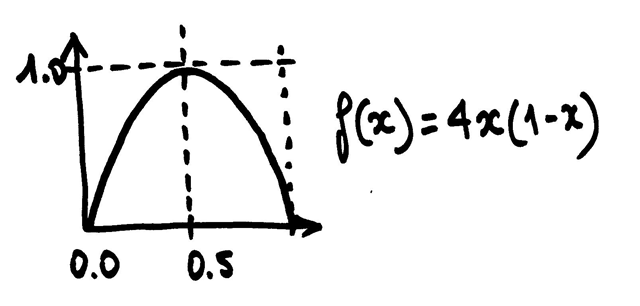

Just to clarify a bit what I have in mind, here is the expression for the logistic map:

x(n+1) = alpha * x(n) * (1-x(n))

This is a recurrence relation, and has been well studied, because it illustrates very nicely some important ideas in chaos theory. In particular, for x0 in ] 0.0; 1.0 [ and values of alpha between 0 and 4, the series will remain in the interval ] 0.0; 1.0 [, and for certain values of alpha, 4.0 for instance, the series will exhibit a chaotic behavior.

Anyways – so here is what I have in mind. If I gave you an arbitrary float in the unit interval, I could “decrypt” binary values this way:

let f x = 4. * x * (1. - x)

let decrypt root =

root

|> Seq.unfold (fun x -> Some(x, f x))

|> Seq.map (fun x -> if x > 0.5 then 1 else 0)

let test = decrypt 0.12345 |> Seq.take 20 |> Seq.toList

Running that example produces the following result:

val test : int list =

[1; 1; 0; 1; 1; 1; 1; 0; 0; 1; 0; 1; 1; 0; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0; 1; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0;

1; 1; 0; 1; 0; 0; 0; 1; 0; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0; 1; 0; 0; 0; 1; 0; 1; 1; 1; 1; 1;

1; 1; 0; 1; 0; 0; 1; 1; 0; 0; 0; 1; 1]

This illustrates how, from a single float value, in this case, 0.12345, I could generate a list of 0s and 1s. The question is, can I generate any sequence? That is, if I gave you (for instance) the following series [ 0; 1; 1; 0; 1 ], could you give me a float that would produce that sequence? And are there sequences that I couldn’t generate by that mechanism?

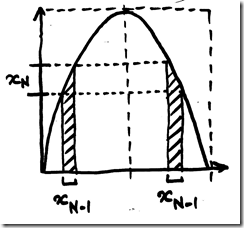

As it turns out, any sequence is feasible. If I start from the last number in the series (1 in our case), the value that generated it, x4, had to be in [0.5;1.0], because it got rounded up to 1. But then, x4 = f(x3), which implies that 4.0 * x3 * (1.0 – x3) belongs in [0.5;1.0]. I’ll let you work through the math here (it involves solving a second-degree polynomial) – what you should end up with is that there are exactly 2 segments that, when transformed by f, result in [0.5;1.0] (see the diagram below for a more visual explanation, illustrating how to find the two segments that f transforms into a given segment x(n)).

Because we know that the 4th value in our series is a 0, we also know that x3 has to be in [0.0; 0.5], so we can just compute the intersection of f inverse (interval(x4)) and [0.0; 0.5], and repeat the process over and over again, until we have finished covering the sequence and reached x0, and we are left with one interval. Any number we pick in that interval will produce the desired sequence.

So how does this look in code? Not awesome, but not too bad. invf is the inverse of f, which returns 2 possible values – and backsolve computes the current interval x has to belong to, given the interval its successor has to be in, and the desired value, a 0 or a 1:

let f x = 4. * x * (1. - x)

let decrypt root =

root

|> Seq.unfold (fun x -> Some(x, f x))

|> Seq.map (fun x -> if x > 0.5 then 1 else 0)

let empty (lo,hi) = lo >= hi

// two inverses, low value then high value

let invf x = (1.-sqrt(1.-x))/2.,(1.+sqrt(1.-x))/2.

// interval = where f(x) needs to be

// binary = whether x is 0 or 1

let backsolve interval binary =

let lo,hi =

match binary with

| 0 -> (0.0,0.5)

| 1 -> (0.5,1.0)

| _ -> failwith "unexpected"

let lo',hi' = interval

let constraint2 =

let x1,x2 = invf lo'

let y1,y2 = invf hi'

(x1,y1),(y2,x2) // this is union

// compute intersect

let (lo1,hi1),(lo2,hi2) = constraint2

let sol1 = (max lo1 lo,min hi1 hi)

let sol2 = (max lo2 lo,min hi2 hi)

if empty sol1 then sol2 else sol1

let solve (xs:int list) =

let rec back bins curr =

match bins with

| [] -> curr

| hd::tl -> back tl (backsolve curr hd)

back (xs |> List.rev) (0.,1.)

Does this work? Let’s try out, by generating a random sequence of 20 0s and 1s, and checking that if we encrypt and decrypt it, we get the initial series:

let validate xs =

let l = List.length xs

let lo,hi = solve xs

decrypt (0.5*(lo+hi)) |> Seq.take l |> Seq.toList

let rng = System.Random ()

let sample = List.init 25 (fun _ -> rng.Next(2))

sample = validate sample

It does work – up to a limit. If you start expanding the length of the series you are trying to encrypt, at some point you will observe that the encrypted/decrypted version stops matching the original. This should not come as a surprise: we are operating in finite precision here, so there would be something deeply flawed if we managed to encode a potentially infinite amount of information, by simply using a float. However, in the world of math, where infinite precision exists, we could transform any sequence of 0s and 1s, of any length, into a segment in [ 0.0; 1.0]. Pretty useless, but fun.

One thing I started playing with was representing segments better, with a discriminated union. After all, the algorithm can be expressed entirely as a sequence of interval unions and intersections – I’ll let that to the reader as a fun F# modeling problem!