Creating an Azure Functions solution diagram

01 Apr 2017One aspect of Azure Functions I found intriguing is that each function contains both its code, and a description of the environment it is expecting to run in, contained in its function.json file. What’s interesting about this, is that as a result, scanning a function app (a collection of functions) provides a fairly complete self-description of the application and its environment, which we should be able to visualize.

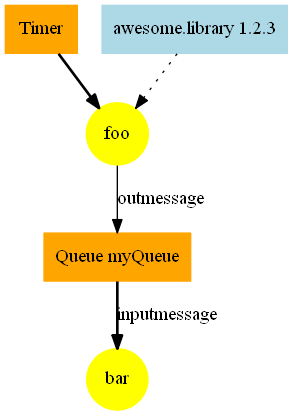

In this post, we’ll explore that idea, and sketch out an approach to automatically generate diagrams, visualizing bindings and code dependencies for a code base. We will only support a subset of the full functionality available in Azure Functions, mainly because we are lazy, and create graphs such as the one below, using F# and GraphViz.

Anatomy of an Azure Function App

Let’s start first with the information we have available. A typical Azure Function App is structured along these lines:

Application

|_ /foo

FooCode.fsx

function.json

|_ /bar

BarCode.csx

function.json

project.json

What we have here is a function app that comprises two functions, foo and bar, identified by their containing folder name. Inside each function folder, we’ll find some code files, exactly one function.json file describing the function bindings, and possibly a project.json file listing package dependencies.

How does a function.json look like? Here is a slightly simplified version from @fsibot:

{

"bindings": [

{

"type": "timerTrigger",

"name": "timer",

"schedule": "0 */2 * * * *",

"direction": "in"

},

{

"type": "blob",

"name": "previousID",

"path": "incontainer/lastid",

"connection": "fsibotserverless_STORAGE",

"direction": "in"

},

{

"type": "queue",

"name": "mentionsQueue",

"queueName": "mentions",

"connection": "fsibotserverless_STORAGE",

"direction": "out"

}

],

"disabled": false

}

The bindings describe how the function interacts with the environment. Each binding has a type (what type of resource is involved), a name (how the resource appears as a named argument in the function), and a direction (in or out). One of the bindings is a Trigger (causing the function to run), identified by a type ending with Trigger, as in timerTrigger. Finally, depending on the type of resource, additional information is provided, for instance a queue name and storage account connection.

Similarly, what NuGet packages a function uses is described in a project.json file, which looks along these lines:

{

"frameworks": {

"net46":{

"dependencies": {

"linqtotwitter": "4.1.0",

"Newtonsoft.Json": "9.0.1"

}

}

}

}

The end goal

So what we want to do here is extract out the information we care about, to create a GraphViz file that we can then process to produce a nice visualization.

GraphViz uses a simple format to represent graphs, which can then be rendered using various graph layout models. A GraphViz model comprises nodes and edges. In our case, we have 3 types of nodes (functions, bindings and packages), and directed edges, representing the direction of the relationship. We also want to distinguish between Triggers and basic in bindings.

Rather than going into a lengthy explanation, I’ll provide an example illustrating what we are after, which should be self-explanatory:

digraph app {

// functions nodes

node [shape=circle,style=filled,color=yellow]

"foo"

"bar"

// bindings nodes

node [shape=box,style=filled,color=orange]

"Timer"

"Queue myQueue"

// packages nodes

node [shape=box,style=filled,color=lightblue]

"awesome.library 1.2.3"

// triggers edges

edge [ style=bold ]

"Timer" -> "foo" [ label="timer" ]

"Queue myQueue" -> "bar" [ label="inputmessage" ]

// bindings & functions edges

edge [ style=solid ]

"foo" -> "Queue myQueue" [ label="outmessage" ]

// packages edges

edge [ style=dotted ]

"awesome.library 1.2.3" -> "foo"

}

I can then simply take this file, and run it through GraphViz, to generate a graph. For instance, dot "graph-file-path" -Tpng -o "output-file-path.png" produces the .png chart we presented earlier on:

Extracting the functions

I will assume here that we have a local clone of the Function App, and will use fsibot-serverless as an example.

In that case, all we need to do is iterate over the directories. If a directory contains a function.json file, it is a function, named after the folder.

open System.IO

let candidates root =

root

|> Directory.EnumerateDirectories

|> Seq.filter (fun dir ->

Directory.EnumerateFiles(dir)

|> Seq.map FileInfo

|> Seq.exists (fun file -> file.Name = "function.json")

)

|> Seq.map DirectoryInfo

Let’s try that out on our example:

let root = @"C:/Users/Mathias Brandewinder/Documents/GitHub/fsibot-serverless/"

let functions =

candidates root

|> Seq.iter (fun dir -> printfn "%s" dir.Name)

>

check-mentions

follow-users

process-mention

send-tweet

It appears that we are in business.

Extracting out the bindings from JSON

Now that we have folders that correspond to a function, let’s extract the bindings from the function.json file. There are 2 parts to the task: grabbing data from a JSON file, and transforming it into some representation for bindings we can work with reasonably easily.

We will limit ourselves to a small subset of the available bindings, and explicitly handle only Timers, Queues and Blobs.

Every binding can be decomposed into 2 parts. We always have 3 properties, name, type and direction, and, depending on the specific resource, we have some additional information available.

We will represent that in a rather straightforward manner:

type Direction =

| Trigger

| In

| Out

type Properties = Map<string,string>

type Binding = {

Argument:string

Direction:Direction

Type:string

Properties:Properties

}

with member this.Value key = this.Properties.TryFind key

A binding can be only one of 3 things: a trigger, an in- or an out-bound binding. This is a natural fit for a Discriminated Union, Direction. Each Binding will contain the three fields that are guaranteed to be present, and we will store all the extra information as key-value pairs in a Map, associating the property name and its value as strings.

All we need to do then is parse the function.json file and create an array of bindings. For that purpose, we’ll use the JSON parser from FSharp.Data:

#I "./packages/"

#r "FSharp.Data/lib/net40/FSharp.Data.dll"

open FSharp.Data

open FSharp.Data.JsonExtensions

let bindingType (``type``:string, dir:string) =

if ``type``.EndsWith "Trigger"

then

Trigger, ``type``.Replace("Trigger","")

else

if (dir = "in") then In, ``type``

elif (dir = "out") then Out, ``type``

else failwith "Unknown binding"

let extractBindings (contents:string) =

contents

|> JsonValue.Parse

|> fun elements -> elements.GetProperty "bindings"

|> JsonExtensions.AsArray

|> Array.map (fun binding ->

// retrieve the properties we care about

let ``type`` = binding?``type``.AsString()

let direction = binding?direction.AsString()

let name = binding?name.AsString()

// retrieve the "other" properties

let properties =

binding.Properties

|> Array.filter (fun (key,value) ->

key <> "type" && key <> "name" && key <> "direction")

|> Array.map (fun (key,value) -> key, value.AsString())

|> Map

// detect the direction and type

let direction, ``type`` = bindingType (``type``,direction)

// create and return a binding

{

Type = ``type``

Direction = direction

Argument = name

Properties = properties

}

)

Let’s test that out, on one of the more involved function.json files from fsibot-serverless - which produces the following:

val bindingsExample : Binding [] =

[|{Argument = "timer";

Direction = Trigger;

Type = "timer";

Properties = map [("schedule", "0 */2 * * * *")];};

{Argument = "previousID";

Direction = In;

Type = "blob";

Properties =

map

[("connection", "fsibotserverless_STORAGE");

("path", "incontainer/lastid")];};

// omitted for brevity

Everything appears to be working so far - let’s move on.

Parsing out package dependencies

Parsing out packages isn’t much more complicated. First, we’ll create a type for Packages:

type Package = {

Name:string

Version:string

}

… and drill into the contents of project.json until we find what we need:

let extractDependencies (contents:string) =

contents

|> JsonValue.Parse

|> fun elements -> elements.GetProperty "frameworks"

|> fun elements -> elements.GetProperty "net46"

|> fun elements -> elements.GetProperty "dependencies"

|> fun elements -> elements.Properties

|> Array.map (fun (package,version) ->

{

Name = package

Version = version.AsString()

}

)

Let’s make sure that this works, on one of the fsibot examples:

val dependenciesExample : Package [] =

[|{Name = "linqtotwitter";

Version = "4.1.0";}; {Name = "Newtonsoft.Json";

Version = "9.0.1";}|]

Done!

Extracting the Function App graph

At that point, we have all the pieces we need: from a directory, we can extract all the potential functions, their bindings, and the packages they depend upon. All we need to do now is generate a file that follows the format GraphViz expects, and we are done.

We create a simple type to store all the information we care about in a function app, and go to town:

type AppGraph = {

Bindings: (string * Binding) []

Dependencies: (string * Package) []

}

let extractGraph (root:string) =

let functions = candidates root

let bindings =

functions

|> Seq.map (fun dir ->

let functionName = dir.Name

Path.Combine (dir.FullName,"function.json")

|> File.ReadAllText

|> extractBindings

|> Array.map (fun binding ->

functionName, binding)

)

|> Seq.collect id

|> Seq.toArray

let dependencies =

functions

|> Seq.map (fun dir ->

let functionName = dir.Name

let project = Path.Combine (dir.FullName,"project.json")

if File.Exists project

then

project

|> File.ReadAllText

|> extractDependencies

|> Array.map (fun package ->

functionName, package)

else Array.empty

)

|> Seq.collect id

|> Seq.toArray

{

Bindings = bindings

Dependencies = dependencies

}

Given a root folder, we identify all possible functions, and then proceed to extract two lists of pairs, one for bindings, associating a function name and a binding, and one for dependencies, associating a function name with a package.

Rendering the Function App graph

All we have left to do now is going over the data in an AppGraph, and creating a GraphViz file, containing 3 types of nodes (functions, bindings and packages), and 4 types of edges (triggers, in and out bindings, and dependencies).

GraphViz maps nodes and edges by name, so we want to make sure our names are consistent; for safety, we also want to make sure all names are surrounded by quotes, to avoid name parsing issues for GraphViz. Let’s create first a couple of utility functions:

let quoted (text:string) = sprintf "\"%s\"" text

let indent = " "

let bindingDescription (binding:Binding) =

match binding.Type with

| "timer" -> "Timer"

| "queue" -> "Queue " + (binding.Properties.["queueName"])

| "blob" -> "Blob " + (binding.Properties.["path"])

| _ -> binding.Type

|> quoted

let packageDescription (package:Package) =

sprintf "%s (%s)" package.Name package.Version

|> quoted

let functionDescription = quoted

We can now create, for instance, the function nodes:

let renderFunctionNodes format (graph:AppGraph) =

let functionNames =

graph.Bindings

|> Seq.map (fst >> functionDescription)

|> Seq.distinct

Seq.append

[ format ]

functionNames

|> Seq.map (fun name -> indent + name)

|> String.concat "\n"

Nothing particularly elegant here - we pickup unique function names from the bindings we identified, format them consistently, and pre-pend formatting information for these nodes (the node [shape=circle,style=filled,color=yellow] in our earlier example).

I’ll skip the rendering of the other nodes, which follows exactly the same pattern.

In a similar fashion, we create the edges between triggers and functions:

let renderTriggers format (graph:AppGraph) =

let triggers =

graph.Bindings

|> Seq.filter (fun (_,binding) -> binding.Direction = Trigger)

|> Seq.map (fun (fn,binding) ->

sprintf "%s -> %s [ label = %s ]"

(bindingDescription binding)

(functionDescription fn)

(binding.Argument |> quoted)

)

|> Seq.distinct

Seq.append

[ format ]

triggers

|> Seq.map (fun name -> indent + name)

|> String.concat "\n"

… and all we have to do now is fill in a template to create a nicely formatted GraphViz file:

type GraphFormat = {

FunctionNode:string

BindingNode:string

PackageNode:string

Trigger:string

InBinding:string

OutBinding:string

Dependency:string

}

let renderGraph (format:GraphFormat) (app:AppGraph) =

let functionNodes = renderFunctionNodes format.FunctionNode app

let bindingrNodes = renderBindingNodes format.BindingNode app

let packageNodes = renderPackageNodes format.PackageNode app

let triggers = renderTriggers format.Trigger app

let ins = renderInBindings format.InBinding app

let outs = renderOutBindings format.OutBinding app

let dependencies = renderDependencies format.Dependency app

sprintf """digraph app {

%s

%s

%s

%s

%s

%s

%s

}""" functionNodes bindingrNodes packageNodes triggers ins outs dependencies

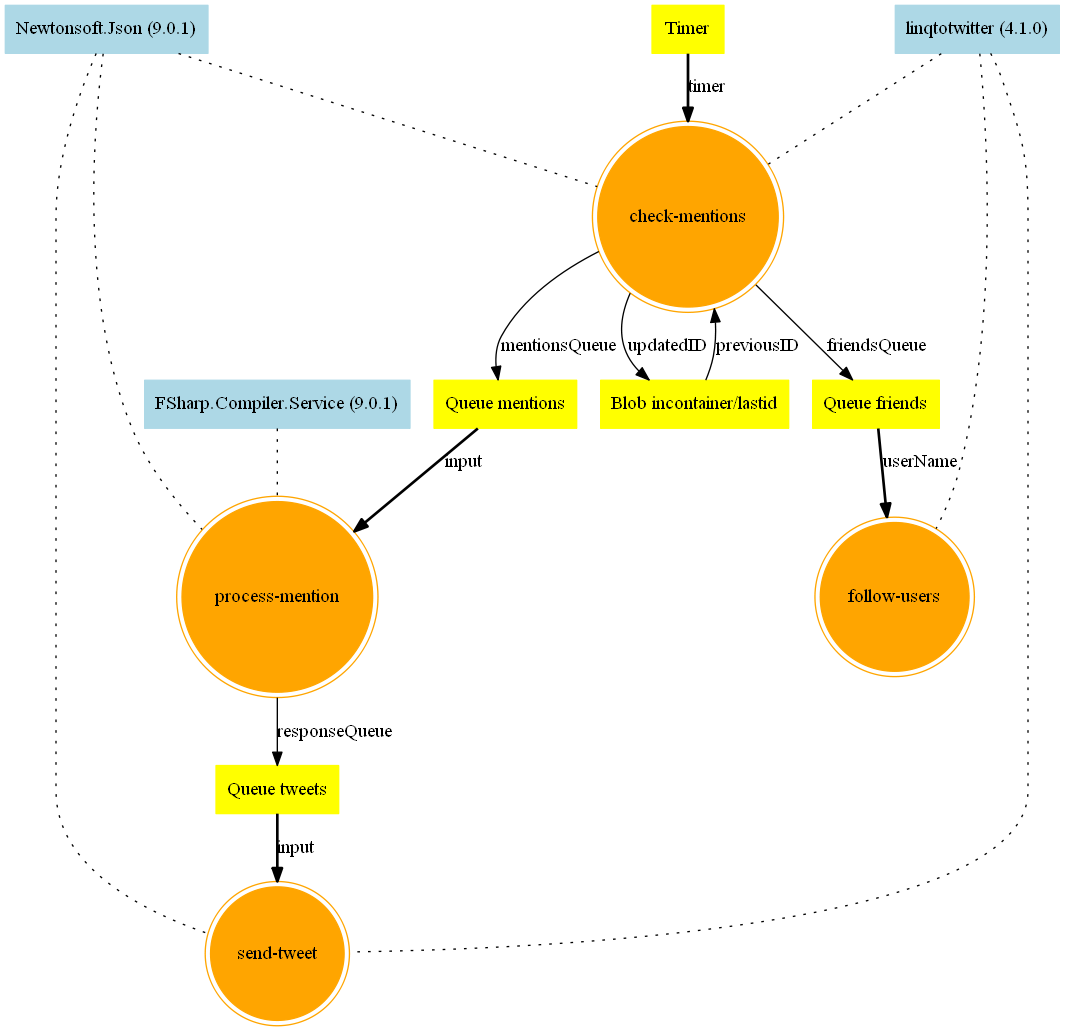

Illustration: fsibot-serverless

So how well does this work? Let’s try it out on fsibot-serverless. First, we’ll create a format for the graph:

let graphFormat = {

FunctionNode = "node [shape=doublecircle,style=filled,color=orange]"

BindingNode = "node [shape=box,style=filled,color=yellow]"

PackageNode = "node [shape=box,style=filled,color=lightblue]"

Trigger = "edge [ style=bold ]"

InBinding = "edge [ style=solid ]"

OutBinding = "edge [ style=solid ]"

Dependency = "edge [ arrowhead=none,style=dotted,dir=none ]"

}

… and then proceed with the full analysis:

let root = @"C:/Users/Mathias Brandewinder/Documents/GitHub/fsibot-serverless/"

root

|> extractGraph

|> renderGraph graphFormat

|> fun content ->

File.WriteAllText(__SOURCE_DIRECTORY__ + "/fsibot", content)

As a result, we get the following GraphViz file:

digraph app {

node [shape=doublecircle,style=filled,color=orange]

"check-mentions"

"follow-users"

"process-mention"

"send-tweet"

node [shape=box,style=filled,color=yellow]

"Timer"

"Blob incontainer/lastid"

"Queue mentions"

"Queue friends"

"Queue tweets"

node [shape=box,style=filled,color=lightblue]

"linqtotwitter (4.1.0)"

"Newtonsoft.Json (9.0.1)"

"FSharp.Compiler.Service (9.0.1)"

edge [ style=bold ]

"Timer" -> "check-mentions" [ label = "timer" ]

"Queue friends" -> "follow-users" [ label = "userName" ]

"Queue mentions" -> "process-mention" [ label = "input" ]

"Queue tweets" -> "send-tweet" [ label = "input" ]

edge [ style=solid ]

"Blob incontainer/lastid" -> "check-mentions" [ label = "previousID" ]

edge [ style=solid ]

"check-mentions" -> "Blob incontainer/lastid" [ label = "updatedID" ]

"check-mentions" -> "Queue mentions" [ label = "mentionsQueue" ]

"check-mentions" -> "Queue friends" [ label = "friendsQueue" ]

"process-mention" -> "Queue tweets" [ label = "responseQueue" ]

edge [ arrowhead=none,style=dotted,dir=none ]

"linqtotwitter (4.1.0)" -> "check-mentions"

"Newtonsoft.Json (9.0.1)" -> "check-mentions"

"linqtotwitter (4.1.0)" -> "follow-users"

"FSharp.Compiler.Service (9.0.1)" -> "process-mention"

"Newtonsoft.Json (9.0.1)" -> "process-mention"

"linqtotwitter (4.1.0)" -> "send-tweet"

"Newtonsoft.Json (9.0.1)" -> "send-tweet"

}

… which we can then feed into the GraphViz command line, with dot path/to/fsibot -Tpng -o path/to/fsibot.png, which creates the following diagram:

That diagram could be improved, of course, but as is, I find it pretty informative already. First, we get immediately a decent overview of the application flow, from check-mentions to process-mention and send-tweet. We can also spot some sort of state persistence happening in check-mentions, with updatedID being pushed to a blob, and previousID being pulled back out from the same blog. We can also see that 3 functions rely on linqtotwitter, whereas process-mentions (where code is being run through the FSharp Compiler Service) has no direct relationship to Twitter, and could perhaps even be isolated into its own App.

Conclusion & random tidbits

That’s as far as I will go on this for now. Before closing, I wanted to comment on a couple of things.

First, while this doesn’t support all the available bindings, it shouldn’t be very hard to add most of them - most of what is needed is adding the missing cases in bindingDescription, to format them adequately. One case that might end up being tricky is bindings that refer to each other (for instance, reading from a table based on a queue message).

Along that line of thought, one potential issue here is that nodes are identified by their name, but name collisions are possible. The identity of a binding comes from its type, and its “additional fields”. As an example, queueName doesn’t uniquely identify a queue; I could have 2 queues with the same name, pointing to a different storage account, but with this implementation, they would appear as one node on the graph.

Beyond that, it could be interesting to extend the graph, and include a few more pieces of information. As an example, we could represent what storage account each of the Azure Storage bindings belongs to, to clarify dependencies. We could also represent precompiled dlls, in a fashion similar to package dependencies.

On a completely different direction, my initial approach was quite different. Without going into too much detail, there were two major differences: I tried to use the JSON type provider, and to represent Bindings using Discriminated Unions, along these lines:

type BindingResources =

| Timer of TimerSchedule

| Queue of QueueInformation

| Blob of BlobInformation

As it turns out, both ideas didn’t work very well. In the end, the DUs didn’t seem appropriate - because they are closed, whereas bindings are extensible - and they added a lot of friction. The Type Provider didn’t fit very well either, and in the end, representing bindings essentially as a bag of string pairs turned out to be much easier.

Finally, I wanted to give a quick shout-out to @thoriumi, who has done some work wrapping up GraphViz from F#.

That’s it - while the code I presented here wasn’t particularly fancy, I hope you found something interesting in this post! And if you want me to post the whole script somewhere, just let me know :)